My pastor has the most creative sermon titles. There is a game that we play at the end-of-year volunteers’ party which(inevitably) includes a question to try to spot the fake sermon title among all the real ones. It is next level difficult. It is in that vein that I label this blog, My Little Pony Dungeons and Dragons though, really, this blog is not about that. Not directly. Intrigued? Read on.

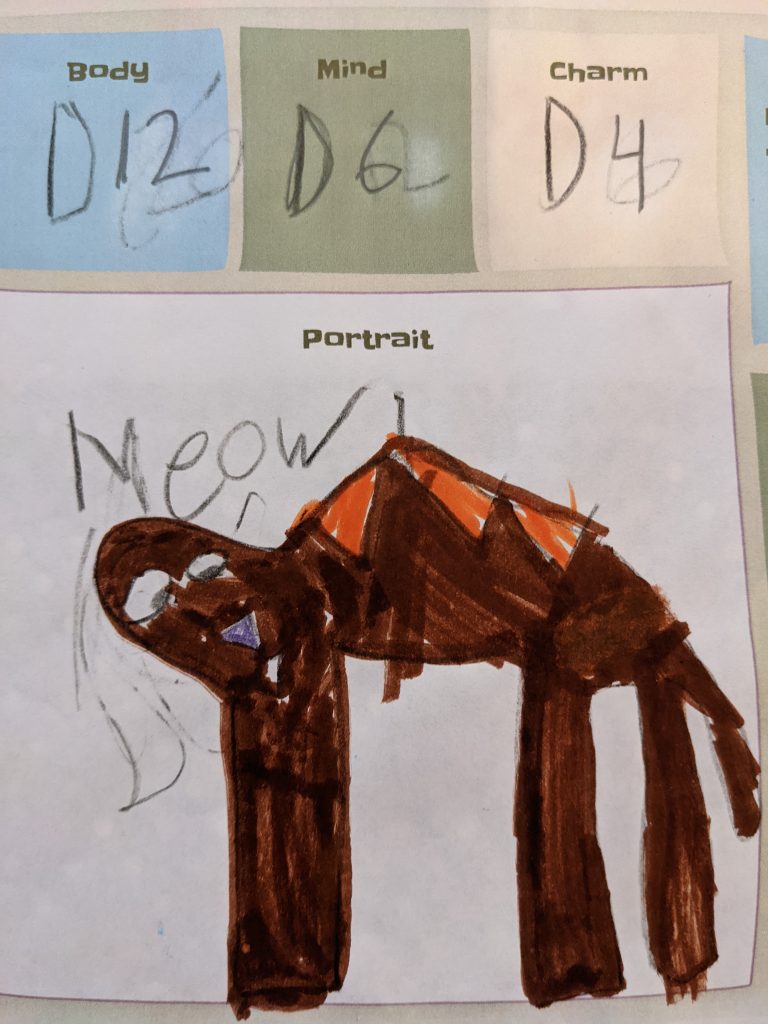

Now that you are (mildly) intrigued, I’ll be honest with you: I have played an adapted form of Dungeons and Dragons with My Little Ponies trying to save the world through the power of friendship. Before you think I’m weird(er than you already know me to be), let me contextualize this as a game that my whole family plays on game night. In addition to the art (see the excellent pony made by my daughter, 4 years old at the time), the math (constantly adding and subtracting dice of various numbers), and the time together, there is story. That is really what this blog is about: story.

Google defines story, in part, in reference to the plot of a thing, what it’s really about. Although our minds might immediately travel to fiction—or ponies protecting the world—in my work as a researcher I find it helpful to think about scientific writing as a particular kind of storytelling. Over the next few blog posts, I tackle scientific writing as story1. (Can you see why I lead with ponies and dragons now? In theory, it has led you read at least this far.)

In this post, I want to introduce you to the basic premise of scientific writing. In future posts, I will explore how to approach the (sometimes daunting) task of writing well and I will frame some ideas around the different components in a scientific paper. If you’re lucky (or, as my dad would say, “a glutton for punishment”), I may even write a blog with some nitty gritty details, sharing examples from a recent paper I wrote (and re-wrote…and re-wrote again).

What is Scientific Writing?

Although you know what writing is, is anything changed by adding “scientific” as an adjective before it? To answer this question, we need to think about science. Science is the study of the natural world. Science describes how things are, explores how/why things work the way they do, and makes predictions about how things might/could/would work, given what we know. Science uses systematic observation—testing, observing, measuring things in the world in strategic and systematic ways—to draw conclusions about the world2. There are many (many!) different empirical methods in science, but they share the common feature of systematic measurement and observation to acquire knowledge. Moreover, science is democratic and cumulative, meaning that debating conclusions based on (and building from) previous research in a public forum is inherent in how science works. The scientific community requires that statements about “the way things are/work” be backed up with verifiable and compelling evidence3.

By this understanding of science, then, scientific writing is the formal documentation of the scientific story with discovery as the core plotline. Scientific writing is how scientists document the verifiable and compelling evidence gathered by members of the scientific community to tell the story about how the world (and the people in it) work. Done well, scientific writing communicates the mystique and intrigue of discovery within the natural world4.

When I conduct a research study, I write it up in a manuscript which is submitted to a journal. The journal will send this manuscript to 2 or 3 reviewers (who are blind to my identity). This process of peer-review ensures that my paper—this piece of scientific writing—is of sufficient quality and caliber to contribute to science and warrant publication. Part of my job in writing the story is to tell the reader what they need to know in a logical, connected way5. (Remember, I can’t just write “this is how the world works: believe me, I’m cool; I play pony-dragons.” I have to, in my paper, document the whole process of my research so that when I ultimately claim that “this is how the world works”, my reader understands how my evidence—the research—led to that conclusion.)

So, in many ways, scientific writing is like all good writing; it differs in its content (an explication of empirically demonstrated evidence), but it is rooted in narratives of discovery.

This narrative of discovery has some formalized sections (i.e., the introduction, methods, results, and discussion sections of an APA paper). However, before we talk about these sections we need to talk about the scientific story writer. Before any words are on (digital) paper, it’s important for a scientific story writer to start with a helpful orientation to the process of writing, an orientation that is highly influential for writing successfully.

While you wait for part 2 (perhaps rolling up your own MLP dungeons and dragons character), I’d like to know: what kinds of experiences have you had with science writing? When I say “science writing,” what comes to mind/what assumptions do you have about what it is/isn’t?

_______________________________________

1As I see it, writing on “writing well” is one of the most daunting topics I could choose. There are many who have written on this, and many who have written on this better than I will do here. Part of the point that I aim to make is that writing is a skill that is developed. That means that, like you, I am in development. However, if I waited until I could communicate about scientific writing skill development perfectly, then this blog would never be written and any potential benefit of this communication, imperfect as it may be, would be lost. As I will encourage you to do: start where you are and commit to developing, uncomfortable as it may be. Your product won’t be perfect, but perfect isn’t a requirement for progress. In writing this blog for you and I’m practicing what I’m preaching.

2Although many students might not immediately associate “psychology” with “science,” it should be clear that psychology is a science, even if it doesn’t share all the methods of natural sciences. That it would have different methods makes sense because it has different a subject matter; surely we can agree that we can (and should) study cells differently than human persons (even if the human persons are made up of cells).

3A very easy introduction to what science is, can be found here. If you are interested specifically in thinking about how psychological science works and fits into science, you can check out this introduction.

4Despite common assumptions, science is not a list of facts about the world. Science includes facts, but it not mainly a compilation of them. As such, effective scientific writing will communicate the mystique and intrigue of discovery, not just consolidate a list of findings.

5This has implications for the actual process of organization and writing that I will address in a future post. My metaphor hear is about maps and directions, but I’ll leave it be for now.

If you found this blog helpful, check out the overview of the whole series here, so that you can find more useful information to develop your writing.