Although cultural encouragement for fresh starts are often reserved for the new year marked every January, the start of a new academic year is, perhaps, a better time for those of us running on a traditional academic calendar to take advantage of a new “year”. With the new academic year comes a new schedule, perhaps a new living situation, new friends, professors, responsibilities….I’m sure your list goes on. With all this new, there is also an opportunity: an opportunity for growth. Maybe it’s about time for you to really prioritize reading the Bible. Maybe you want to finally run that 5k or eat the vegetables your doctor says you should. Perhaps you just want to have better relationships this year. Luckily for us, psychological science has a lot to say about how to make the most of these kinds of opportunities. Here I want to share just a few of these evidence-based practices for real, lasting change.

1. Set the right kind of goals.

Spoiler alert: The kinds of goals we set are directly related to the outcomes we attain.

There is lots of research parsing this specific statement apart, specifying it, supporting it, and fine-tuning our understanding of it. For example, goals that emphasize growth and progress over perfection and demonstration lead to better outcomes[1]. Pursuing goals that are inherently meaningful to you, that you choose freely, are associated with a host of better outcomes for the goal itself, and for associated well-being. Factors like specificity of the goal and affect, among others, also influence how successful goal pursuit will be.

Much of the research on goal success is organized around what researchers call the “SMART goal framework.” SMART is an acronym for Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Time-bound. Oftentimes, New Years’ Resolutions (or new academic year opportunities!) fail because we never turn our “good ideas” into “actionable ideas.” Take, for example, someone who has the admirable idea of wanting to be a better student this year. As a professor, I say, ‘yes! Pursue that!’, but then I have the SMART goal follow-up: How? What would being a better student look like for you? What kinds of behaviors are associated with the success of that goal? Perhaps it is reading all the assigned work for your social psychology course prior to the lecture date and committing to studying, review, and assignment completion for that class three times a week for 1 hour each session. Those statements are specific (read what has been assigned, study for three 1-hour sessions), measurable (at the end of the week, did you do it? Yes/No), attainable (this will depend a great deal on your own schedule, but I would suggest that if you don’t have three hours a week to devote to studying for a class, you may have too much on your plate[2]), relevant (completing course reading, assignments, and studying is surely part of being a good student), and time-bound (this goal will conclude at the completion of the course, since you don’t need to study for a class that has finished!).

It turns out that when we take the time to translate good ideas into SMART goals, we are much more likely to accomplish them. One potential reason is that SMART goals, when well-constructed, force us to face our reality honestly. For example, for someone with limited physical fitness it wouldn’t be an attainable goal to run a marathon at the end of the month. Sometimes it is hard to know if your goal is indeed structured well in this kind of formula; keep reading (especially tip #4!).

2. Consider Gold, Silver, and Bronze Medal Goals[3]

One problem, especially for perfectionists out there (seriously, go read Carol Dweck’s book, Mindset), is that goals are often framed as a “pass/fail.” You either did it or you didn’t. This, on its own, can actually be de-motivating. Folks who have tried to eat better by restricting all kinds of “bad” foods can experience this; one slip up can often lead to a downward spiral of out-of-control eating of the supposed “off-limits” food. This kind of black-and-white approach to goals is inherently self-defeating.

So, how do you set measurable, specific goals that also have room for grace and failure? One way is to have “tiered” goals: a gold medal, silver medal, and bronze medal goal. You want to start exercising? Maybe your gold medal goal is a SMART goal for exercising 5 times a week for 30 minutes [4]. So what about that week that every class has a paper due, your car breaks down, your best friend has a crisis….what then? Is your goal doomed? Maybe not. What if you can still make it to the gym 3 times that week for 20 minutes? That can be a silver medal goal. Because those days and minutes are better—in terms of moving you toward your ultimate long-term goal of an exercise habit—than nothing. And if you didn’t make three times…what about one day? Or intentionally taking a parking spot that is crazy far away and sprinting to class or chapel a few days a week? Might that count as something, perhaps a bronze medal goal? Having thought through various levels of achievement allows you the flexibility to view “near hits” of a goal not as a miss, but as a different level of achievement. The more successes you have, the more likely you are to continue in your goal pursuit because intention to achieve a goal alone is insufficient to actually achieve that goal.

3. Understand your time.

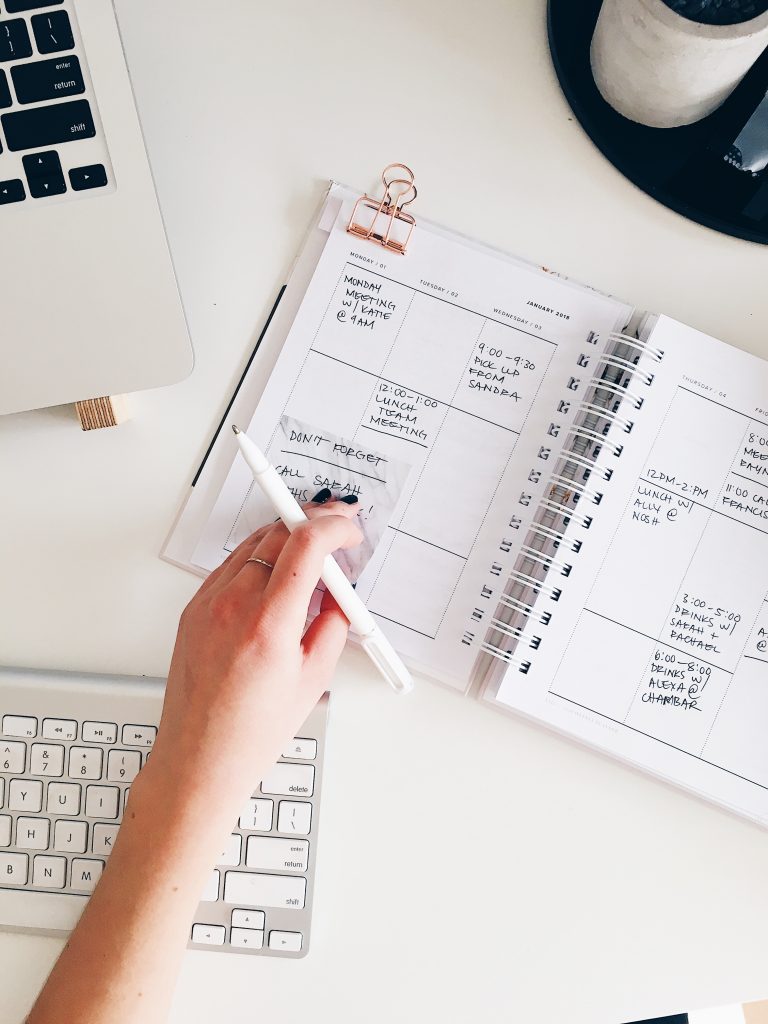

In order to set effective goals, given the parameters above, you need to have a clear understanding of how much time you have and where it is spent. You can’t honestly assess if it is realistic and attainable to exercise 5 days a week for 30 minutes or take on that part time job for 15 hours a week or spend 45 minutes each morning in Scripture and prayer if you don’t have an accurate handle on your time.

…we also need to be realistic about the time we have and the goals we chose to pursue in that time.

Time management skills are an important predictor for many goals, including academic success. The more we think about time as a resource, the better we can steward it. Just as we wouldn’t build a tower without first counting the cost (Luke 14:28), we also need to be realistic about the time we have and the goals we chose to pursue in that time. I find the visuals here to be helpful: time is fleeting. Understanding and using it appropriately (perhaps a topic for a different blog) is key. By sitting down and being honest with how you currently spend your time and how you can reclaim it in pursuit of your goals, you are (once again) adding to the stack of influences increasing your odds at goal achievement. As you prepare for a new semester, spend some time charting time in class, time at work, time studying/doing coursework, time eating, time exercising, time spent with friends…This kind of reverse engineering is an important reflection of what you are able to pursue, but also how what you pursue reflects about your priorities, as you live them.

4. Seek wisdom

Sometimes it is hard to know if the thinking inside your head makes sense outside your head, or how to make the most of the time you have. (I’m just going out on a limb here, assuming that’s not just me.) Thankfully, we don’t do this life thing alone and, as Christians, we are specifically called not to! As you think about what opportunities the new semester presents to you, what habits might need to change, and how best to change them, don’t have that conversation in a vacuum. Seek counsel. Bounce ideas off trusted friends. Ask a mentor for feedback on your goals. Visit a faculty member you respect during office hours. It might sound scary or a bit vulnerable to do these things but consider Proverbs 4:7: “The beginning of wisdom is this: Get wisdom…”. I love this. You want wisdom? Get it. But how—you can’t use what you don’t have! I believe the Biblical answer lies in community; seek those who have wisdom and in those relationships, get it. What better place to start than questions around how to improve your habits, habits which are the core of your character.

One important caveat: be strategic in your accountability. Turns out that there are some unexpected consequences of sharing your goals, some of which can actually decrease the likelihood of goal achievement. However, when you choose whom to share your goals with carefully, such as sharing with a trusted friend of mentor, the effect of accountability serves to increase the likelihood of goal completion. In many ways, this mirrors what Scripture says about wisdom: you can’t get it from someone who doesn’t have it. To pursue it, you need to first go to the few who have it.

Most of these tips fall under a large umbrella called motivational science. This literature has a lot more to say about how to produce lasting change successfully. Check out some of the links above and explore the rabbit-hole of internet knowledge. However, even without traveling that rabbit hole, I hope that you will take some of the cues in these tips and realize that you don’t need to know everything in order to make small changes. (That’s right: you don’t need to be an expert in motivational science to benefit from the knowledge it has produced.) Big changes are, after all, often just a series of routinized small changes.

With that in mind: where can you start fresh this academic year? What habit(s) need revision? Need better study habits? To prioritize your relationship with God? To take your eating or exercise habits more seriously? Or perhaps you need to develop better relational capacities. Whatever the change is, I hope that these tips will provide a starting point for thinking about how to make that change and make it last. I also hope that you will check back to this blog and check out some of the curriculum in the College of Behavioral and Social Sciences here at CBU, as both will offer specific tools to help you in this journey.

Where can you start fresh this academic year?

As an added incentive for you to think about these questions, leave a comment below: where are you hoping to start fresh or what evidence-based tip above did you find most helpful? One comment from a current CBU student will be selected at random to win a CSHB power bank….you know, to keep your cell phone charged and ready to check back for more blogs, all semester long.

Update: Comments are working again! Please comment below. For the hassle, we’ll give away an extra power bank to a lucky CBU student!

Note: We will be giving away power banks all semester when you read and engage with new blogs, so be sure you check back for new blogs and leave comments! Raffles will be held a week after the blog is posted. Please email CSHB@calbaptist.edu if you have any questions.

[1] This is a statement I’m particularly passionate about. There is a wonderful book on this topic, accessible to a non-technical audience, that I would heartily recommend. Check out more information here: https://mindsetonline.com/whatisit/about/index.html

[2] As a note on time: each unit of a course translates to 2 hours expected outside that course a week. Thus, a typical 3-unit class expects 3 hours in-class engagement and 6 hours out-of-class engagement in a typical week. Thus, the estimate above is actually a low estimate of expectation.

[3] Thank you to Dr. Iverson for sharing this model with me and a former Introduction to Psychology course.

[4] Keep in mind that the more specific you can make “exercise”, the better (e.g., cardio? Weight lifting? A GroupX PiYo class?).