By E. Russ Bermejo, MSW, Lecturer

Note: In my previous blog entitled Pouring Gold into Brokenness: How Japanese Art Shows Us the Way, I shared how author and artist, Makato Fujimura uses two ancient Japanese art forms to illustrate how fragmentation presents us with a choice: We can either be artists making something new or we can hide in our silos missing any chance of being part of a something beautiful. I closed Part 1 reflecting on my career in child welfare and the need for us to be better by working together for some of the most marginalized families in our communities.

In Part 2, I offer a mirror and window for us as Christian scholars to look at. My hope is that we “part-take in the co-creation of the New.” Thank you for reading.

Academic Silos

Unfortunately, much of the siloing we see at the organization or systems-level begins to some degree in higher education and academic settings. Peter Senge, systems scientist and most known as the author of “The Fifth Discipline – The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization” (Doubleday, 1990) notes that true learning organizations pride themselves on shared learning. Unfortunately, silos develop when a product or service is successful. Consequently, the more successful the silo, the higher the walls. Senge warns that success and pride suppresses innovation and collaborative experimentation outside of the silo. This happens when you see learning and knowledge as proprietary or a commodity to be protected. Senge explains that educators and higher ed institutions, unfortunately, oftentimes can have the tallest silos and be the least innovative by focusing on deep learning rather than engaging in interdisciplinary ideas and solutions.

But maybe there is a different path? Just as nihonga is impossible to teach outside of the artisan ecosystem, perhaps we can say the same about our respective disciplines. It is impossible to teach social work without including the disciplines of psychology, sociology, education, public health, law, business, economics, etc.

Higher education must continue to adapt to an ever-changing world and explore how we are to educate our students to become the kind of citizens of a local and global community that is highly complex and interconnected, yet broken and fragmented. We have the opportunity to shape the next wave of leaders who can see the world in new interdependent ways and draw from perspectives of many disciplines.

Here are some ways we can do this:

- We can help students become better analytical and critical thinkers. Rather than disseminating and depositing knowledge resulting in passive consumption of knowledge, we can help them become innovators, problem-solvers, and “makers of knowledge.”3

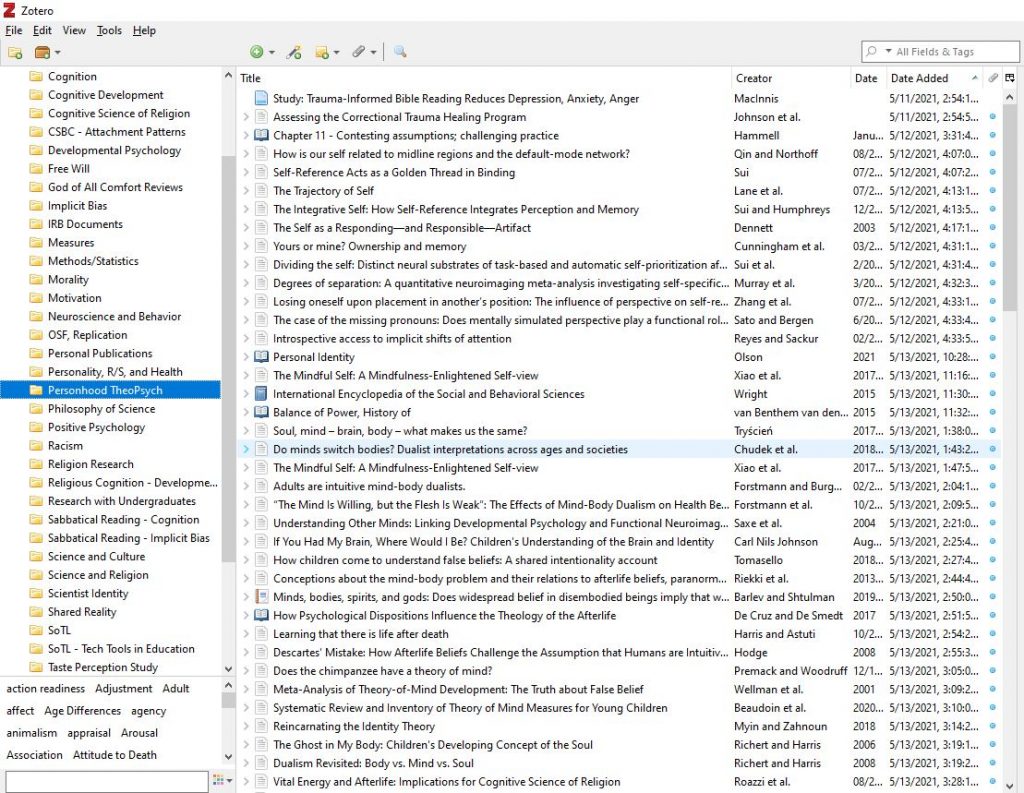

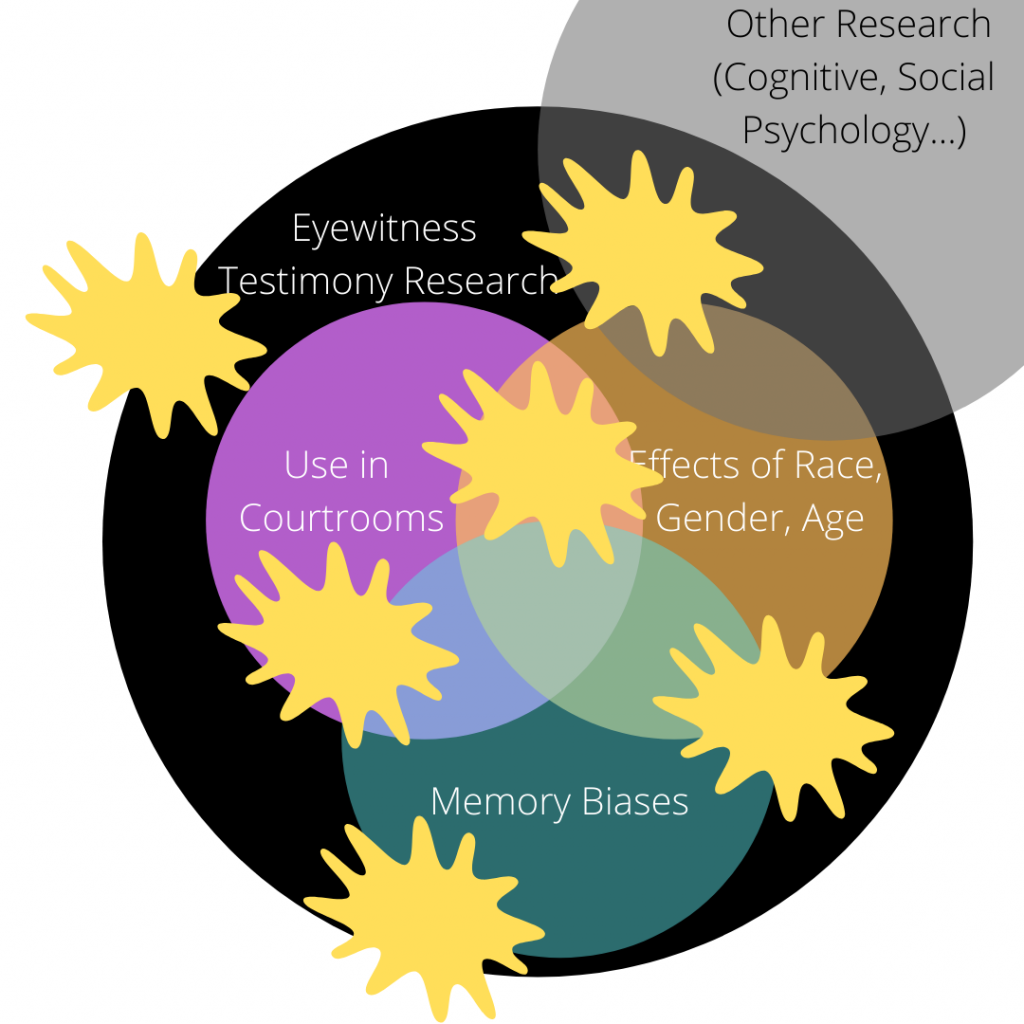

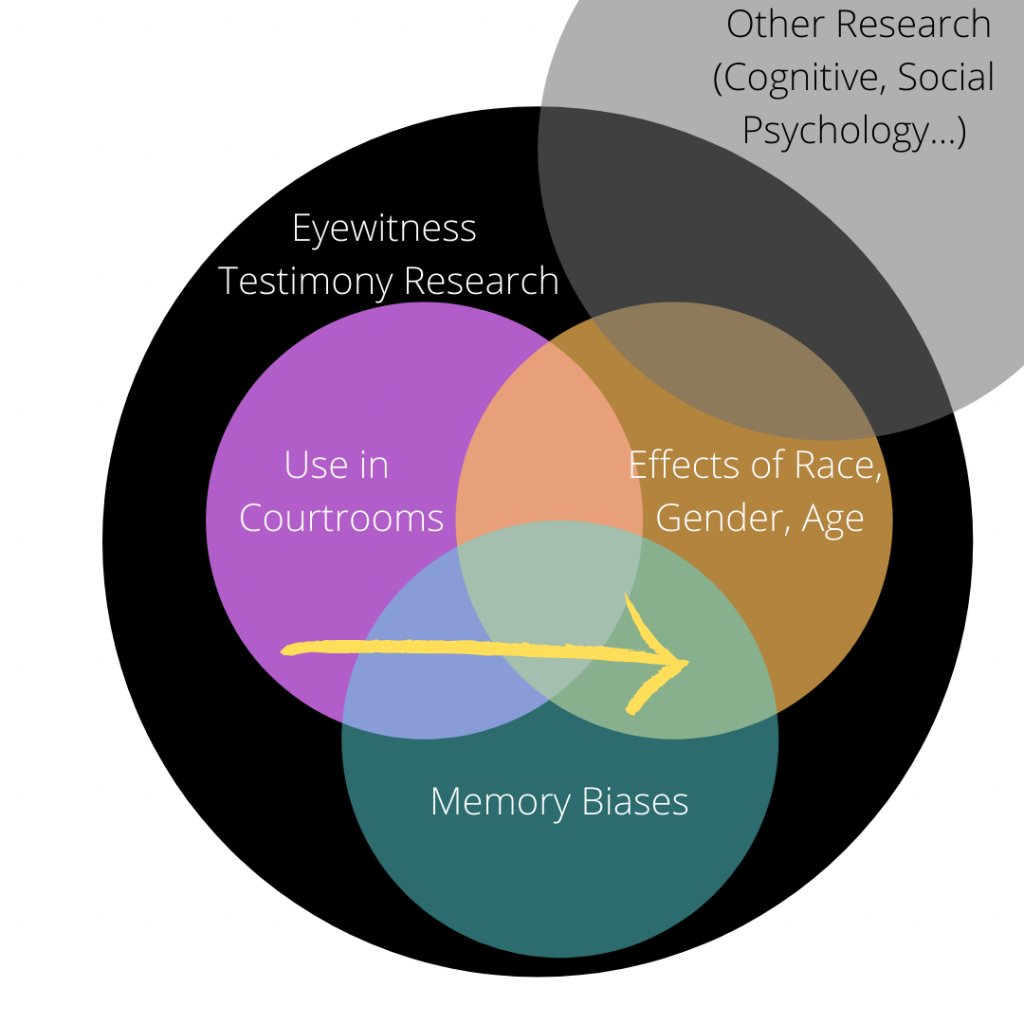

- Next, we should continually look for opportunities to model for students how to engage in informed and collaborative interactions with other disciplines. These interactions can range from guest lectures, interdisciplinary seminars and symposiums to scholarly activities, including research.

- Some academic and professional communities have established interdisciplinary research centers that gather scholars from other departments, universities, and institutions to engage in innovative solutions to the most pressing problems in local and global communities. The Center for the Study of Human Behavior is a prime example of how our college is demonstrating how we can unify diversity in scholarship to achieve common goals. What would it look like if the behavioral and social science research community at every university4 took the lead in breaking silos and use research and partnerships to eliminate disparities and inequities in their local community? This would certainly be a beautiful thing.

How can we lead the way?

The Body of Christ – Leading the Way

The good news especially for us here at CBU, as a part of the Body of Christ, we are uniquely positioned to lead the way towards kintsugi integration.

First, we must remind ourselves of our own brokenness and recognize that our Maker came not to merely “fix us” but to make us into a new creation. Each of us suffer from past, current, and future wounds of pride, ego, power, discrimination, injustice, or inequality. Instead of seeing these as things to be fixed, kintsugi integration illuminates the path through unity and beauty. Just like the fissures of a kintsugi bowl is an opportunity “waiting to be created” we are shards waiting to be made new again.

According to Fujimura, “the heart of the Theology of Making is not only are we restored, we are to part-take in the co-creation of the New.” We have what we need to be makers because we have the innate impulse bestowed by The Artist and Creator to create.

As Christian scholars, we recognize that we have a unique role in the Body (Ephesians 4:11, I Corinthians 12:12-13) yet we are “all one in Christ” (Galatians 3:28). We see diversity as necessary for our thriving and making; our community is not derived from likeness, but rather a “common-unity” of knowing that we are made in His image and have a common mission (Matthew 28, 18-20). Paul writes in Colossians 3:10, “And have put on the new self, which is being renewed in knowledge after the image of its creator.”

As a body of faith, we are an ecosystem of artists ready to create and also key ingredients of a masterpiece ready to be unveiled.

Finally, as Christ followers, we should be motivated not by ambition, status, or success but rather by the humility of Christ, who “humbled Himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross” (Philippians 2:8). As someone who is just starting his career in academia, I am reminded that if I’m preoccupied worrying about status or success in my discipline, I may not live out my purpose set forth by my Maker.5 So my focus must stay fixed on the Cross, our greatest reminder of how Someone poured gold into our brokenness.

Just as Fujimura observed in the Rembrandt and Picasso paintings, a test of our faith demands us to choose – will we turn to our inward selves, hide in our silos and wear masks to uphold a strong ego, or will we die to self so we can live in Christ – for His fame and glory? For Fujimura, he chose the path of joy, faith, and light. We should follow and do the same.

__________________________________________________________

3In his book Super Courses – The Future of Learning and Teaching (Princeton University Press, 2021), Ken Bain presents an innovative way of teaching that inspires students take control of their own education and motivate themselves to think through all of the implications, applications, and possibilities of what they learning. These environments involve heterogenous student groups and allows educators to “break down the walls between academic disciplines and help students combine areas of studies to tackle important questions.” To learn more, click: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2021/03/31/authors-discuss-what-makes-super-course

4The word “university” is derived from the Latin universitas magistrorum et scholarium, which roughly means “community of teachers and scholars”. Imagine a uni-versity campus uni-fied with a common-unity.

5I’m currently reading another perfect book at the perfect time –“The Flourishing Teacher –Vocational Renewal for a Sacred Profession” by Christina Bieber Lake (Intervarsity Press, 2020). The author also created an online fall retreat, which I’m currently doing. I would love to engage in discussions about this book with other faculty. For more information, please visit the author’s website: https://christinabieberlake.com/