Weaving Without Numbers: The Literature Review: Scientific Writing – Part 4

In my previous blogs in this series on scientific writing, I have covered what scientific writing is, the characteristics good writers develop, and the basic structure/purpose of different sections of a scientific paper. This is all well and good (well, at least I think it is….and you’re still here, so I’m hoping you do too), but I’ll venture that at least one of you is thinking, “but how does this apply to the paper I have to write this semester?” (I’m looking at you, Psy 328 students.) In this blog and the next, I want to focus on a specific kind of science writing, the kind that most of you will encounter as your run of the mill “research paper/literature review assignment.” Today, I will focus on conceptualizing a literature review; in the next post I will pull back the curtain on a recent literature review I wrote and walk you through my process.

The Literature Review

A literature review is a summary and synthesis of what other researchers have studied and found about a specific topic. This differs in important ways from the introduction-methods-results-discussion format I discussed previously. Literature reviews bring together different programs of research or theories or they synthesize research in a way that suggests new ideas or theories. The goals of a literature review will vary as a function of the intended audience; effective writers (of all stripes, not just science writers) know who their audience is, and they communicate directly to them, an issue I take up in my next post. Literature reviews are a key staple of any body of research (or, thinking in the metaphor from my last blog, a section of tapestry) because they provide an overview of that part of the tapestry.

Literature reviews do not have all the sections of the APA style paper but share the end goal of describing how bits of the tapestry (our knowledge, as informed by emerging and ongoing research and analysis) fit together. Literature reviews are a type of research papers without original data and are thus, at their core, conceptual. To write an effective literature review it is vital to know what you want to say and bring in appropriate evidence (other people’s research) to build your case. A literature review isn’t driven by or organized around a specific set of data but rather the idea(s) of the writer. When writing a literature review, a very common type of paper assignment in college, you need to be able to clearly answer the questions:

- Why would someone read this paper/what should they know/think when they are finished?

- What is the thing that you have to tell them?

As you will see when I share my process in the next blog, I find the process of writing to be utterly instrumental in the development of how I answer these important literature review questions. If you don’t have a clear idea of what you want your reader to know when you start writing, you should, at minimum, know after numerous rounds of revision. By the time your paper is finished you should be able to share in a sentence or two the “big picture idea” that your paper is engaging. (This is why you should always, always (!) write your abstract last. If you write your abstract first, you should have to re-write it to reflect the final organization which will change through the process of writing and revision.) If you can’t summarize your big idea in a few sentences (the famed “elevator pitch”), I would question whether you have a clear and focused idea of what your paper is about.

Keep in mind that your words-on-paper are the only access that your reader has to your thoughts. No matter how brilliant your thoughts are, if your reader can’t fully discern them from your words-on-paper, your thoughts will be unable to make the desired impact. For me, my revision process is, in part, how I decide what I want to say (i.e., do I need to explain this more? This bit of information is interesting, but does it enhance my story or is it tangential to it?). My revision process also helps me focus on whether I am organizing my thoughts in a way that achieves my goals (e.g., communicates my ideas and thoughts).

Once you know what you want to say in a literature review, remember that the research needs to be presented in a way that tells a story, the story of the thing you want your reader to know. If you are telling a story, that means that every citation, idea, or theory you include has a purpose—to advance, nuance, enrich—the storyline. Citations are the evidence of the thing you have said. Each sentence should contribute to the developing plotline of discovery you are leading your reader on.

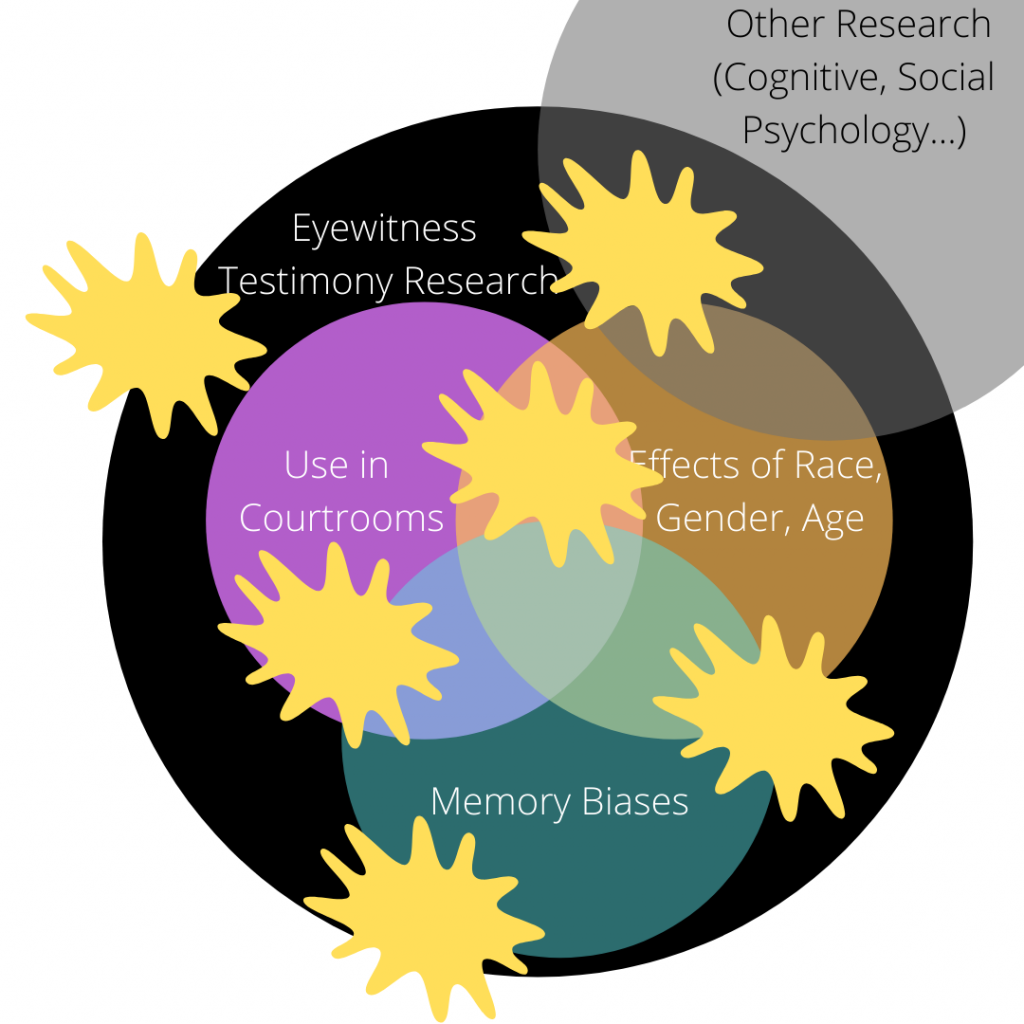

Take, as an example, a literature review on “eyewitness testimony.” This is a massive topic with lots of research exploring different aspects of eyewitness testimony. If you were to go to google scholar or the library database and search “eyewitness testimony” you will get a ton of sources exploring the many dimensions of eyewitness testimony. You might find some about how it is used in a courtroom, how race, gender, and age influence accuracy, and a whole host of memory biases that we need to consider. Yet, the quantity of sources says nothing about whether these sources should all be grouped together in this paper that you are writing. Just selecting a few and talking about them consecutively does not tell a good story. Imagine a paper that looked like an exploded paintball on the diagram below; the splatter (each citation/idea) is random, only loosely connected to the (very broad) concept of “eyewitness testimony.” As the splatter is random, so is this kind of paper.

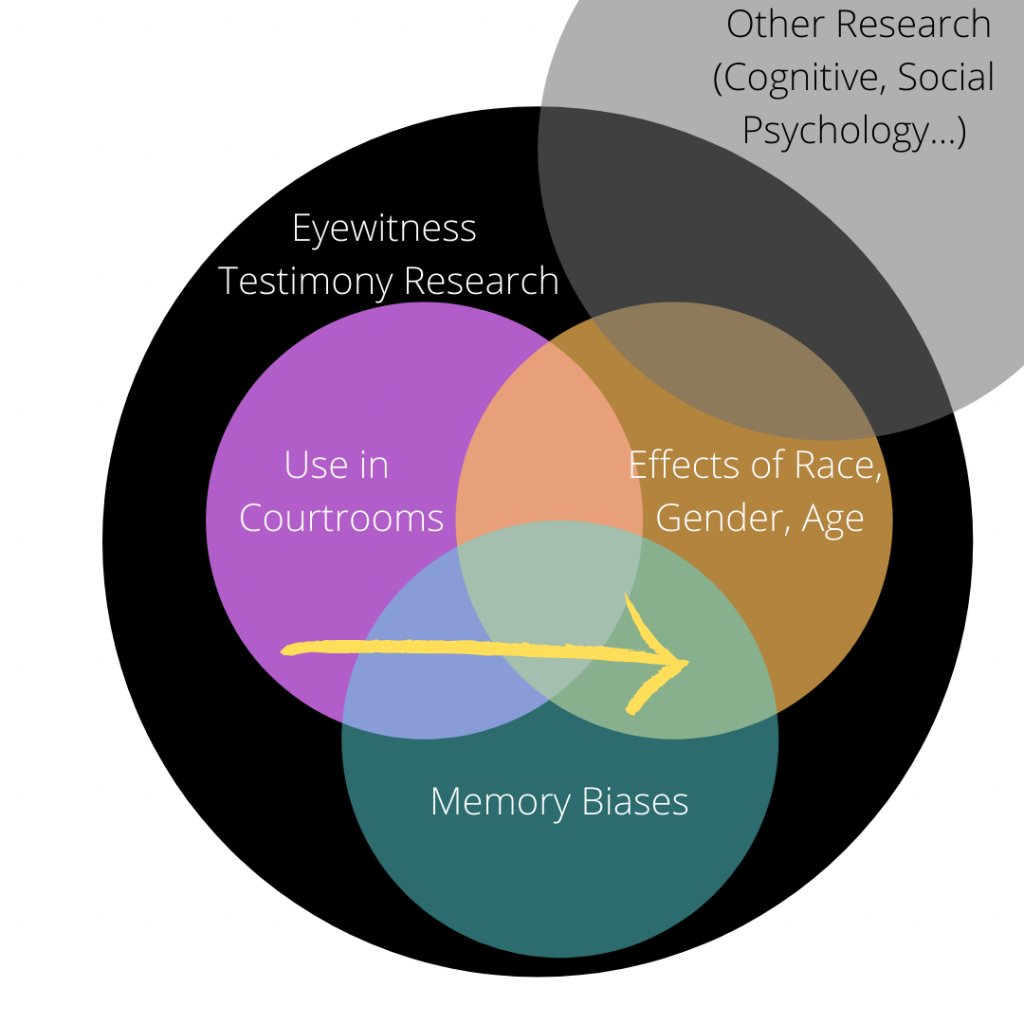

What you want to do in any literature review is have a clear idea of your focus (for example, where the yellow arrow is pointed in the diagram: a paper on how race, gender, and age interact with memory biases to influence eyewitness testimony). In this example, such a focus will help you determine to include only the research on race, gender and age on eyewitness testimony that overlaps with research on memory bias. There will be a lot of research on race, gender, and age as well as memory biases in eyewitness testimony, but when you have clarified that you are focusing on where they meet, it will help you know when to exclude interesting research that is not laser focused on your relevant topic. Such a focus is a really important first step (one that can emerge in the organization and revision of the paper as writing can refine the focus), but keep in mind that you will still need to organize the ideas in a way that is coherent, logical, and persuasive (more on that in the next blog).

As I will tell my students: there needs to be some reason to include all of the citations, ideas and theories in your paper. Why are they together in these pages? To answer this question, you need to have a clear focus of what your paper is about and what it might be related to, but also what it is not about. This kind of clarity will guide the sources and ideas that you include as part of your discussion and the choice to not include one. The papers and ideas in your paper should hang together to help guide your reader to your ultimate conclusion: an understanding of whatever the thing is that you want your reader to know.

Sneak Peek

As a bit of a sneak peak, I’ll tell you that in the next blog, I plan to pull back the curtain on a paper I wrote just this year. The paper, titled A tale of two perspectives: How psychology and neuroscience contribute to understanding personhood, is one that I started thinking about in January, 2021. I did all the reading and writing for the paper, start to submission, in the month of May, 2021. (A timeline not too unlike a typical semester paper assignment.) I have since learned that this paper was accepted for publication (after some formatting fixes and a required reduction in word count)1. In the next post, I’ll guide you through my process by sharing my notes and behind-the-scenes revisions with commentary on my process. My goal is to share some nuts and bolts for how I go from an idea-in-head and a stack of articles to a science story. I’ll address the question of “do these ideas hang together, given my audience?” mentioned above and tackle the question of “where (and how) do I start?”

Although I want you to stay tuned, I’d also like to hear from you: do you like writing literature reviews? Why or why not? What is the hardest part for you? Share your thoughts below.

____________________________________________

1I will add a link to the paper here once it is finally published (a process that usually takes longer than we think it should…).

If you found this blog helpful, check out the overview of the whole series here, so that you can find more useful information to develop your writing.

22 Comments

Hi Dr. Smith!

To be honest, I never liked literature reviews because I think many teachers in high school never explained their purpose to me. I always felt like they were so unnecessary and I always tended to choose article randomly, just so I could write them in. I think the hardest part is taking the time to really understand the themes of the articles in order to represent them well in the literature review. However, many of my college professors (including yourself) have really helped me see the value of literature reviews. I still feel that my literature review skills could use some work, but I am hoping that I will be able to grow in that! Great article!

Thank you! Learning takes time, but you are right: understanding the point is the first step! Glad I can be a part of your own journey.

Hello Dr. Smith,

An excellent post on Literature reviews, how they are a mesh of ideas coming together to form one hypothesis. I compared your meshing of ideas to a pot of soup, they both have many ingredients being mixed into one pot (or paper), to make a well formed meal. But, often times it takes a few revisions to make a recipe perfect, much like for a scientific paper. I also really liked your note on how this paper and its words are the only access the reader has to my thoughts, so I need to make it clear and concise so that they know what I am trying to convey to them.

Yes! There are lots of good analogies. One thing that also matters in recipes? The order you add ingredients. The same is true of writing a literature review: you have to lead your reader down a meaningful (well-ordered) path, you can’t just throw ingredients at them and hope the soup comes out. That is a really critical point: does the order of what I’m communicating make sense?

The first time I had to write a literature review was in college. I thought to myself why do I do have to do this and what is the purpose? As I wrote the literature review I began to start to understand the significance. I do not mind writing them as much anymore because it also helps me understand the literature more clearly! The hardest part is the actual research to find the correct literature.

Finding the research is its own set of skills (which, you may not be surprised to learn is also developed with practice). Just keep at it!

Hi!

I’d have to echo some of the other replies in that I myself have also not appreciated literature reviews or the value that they can hold when executed and digested correctly. I think there’s a lot to be said for the way someone chooses to perceive things like literature reviews, and that they see them as educationally valuable as opposed to seeing them as solely a chore or a thing to check off the list.

I loved the things that you had to say!

Josh

Thanks for sharing Josh! Literature reviews are my *favorite*!

Hi Dr. Smith,

It was not until my last year of college in which I learned about in-depth research papers. I had come across a few of them here and there, but I never knew how to actually write one. Abstracts, introductions, methods, results, discussions, etc. were all new to me and I was extremely overwhelmed and still am at times. However, I am so glad I have come across this blog because all of the tools I have read are extremely helpful and easy to follow. It is not all a bunch of information that leaves me more confused. A literature review seemed like the most difficult thing to accomplish and lectures can only help so much. I will be referring back to these posts when I need to because I am positive it will make the writing process a lot smoother. Thank you.

Wonderful! Glad you have found it helpful!

Hi Dr. Smith, thank you for this great post! I took your Introduction to Psychology class when I was a Freshman, and now I am a Senior. I only wish I could have read your posts on Literature reviews before I began writing mine because this was so helpful. I remember struggling with seeing my literature review as the first step to my entire research assignment because, at the time, my literature review felt like such a huge assignment. I appreciate the way you described the paper as a summary of what other researchers have found on my topic. I wish I had viewed my paper as more of a way to explain why my topic is so important instead of trying to make it sounds so finalized. Even tips like writing the abstract last are extremely helpful because you never know when you’re going to have major changes to your topic until you’re done with the paper. Again, thank you for the helpful post!

So glad you found this helpful, Danielle! I appreciate that feedback and am so glad you shared it.

This provided great insight into how I can improve the cohesiveness of my papers. I struggle with conveying my thoughts, and after reading this post, I realized it has a lot to do with how my literature view section. I need to make sure I stay on topic and only discuss things that overlap with my main focus.

Yes. One thing that collaborative research has taught me is how to stay focused. (Other eyes on your ideas make us better able to identify our blind spots.) Just becuase something is interesting, doesn’t mean this is the place to say it!

I absolutely hate literature reviews reading them, writing them, hearing about them. ANYTHING about literature reviews. I don’t care what the authors have found because if I am reading their paper I most likely I have also already seen that article/research and same with anything I might publish. I understand their literature review could make my life easier, but I still think it is a waste of space in research and too time consuming.

Hello Dr. Smith,

As daunting and time consuming as the literature review was, I think it was essential to the project as a whole to read all of that relevant research. I could not have developed a hypothesis or created a good survey without looking at the research I found for my literature review. Despite it’s benefits, I would not say that I enjoyed it as it is so time consuming and just difficult to do as a whole. However, I can see all of the benefits of it.

Thank you for sharing your experience with literature reviews! Good to hear that even though reading the research can be a bore, it helped you to develop a hypothesis and great survey!

Literature reviews in higher education are much much different than the literature reviews we wrote in my senior AP lit class in high school. When we first started researching topics to to conduct our surveys and study on in the first stages of the BEH sequence, it was so overwhelming. Alongside this, having to read the literature in the library database was hard, it was a lot of numbers, statistics, and oftentimes did not match the hypothesis I was trying to refine. This caused a lot of scratching out a lot of sources and continuing to look for others, which took a lot of time and effort. I will say, because of this I feel like I am a better reader of literature reviews and writer from all the research I’ve read, even outside of what I am studying.

Such a good observation. The post I just published today deals a little bit with the “what about when the research doesn’t match what I think it should?” Part of the writing process (be it empirical or a literature review) is being open enough to have our ideas changed. It’s hard, but it’s so important. I try to budget in time to walk away from what I’m writing to give myself the time to let ideas settle. (And to proof read with less tired eyes 😉 )

Lanna, thank you for sharing your journey with literature reviews! It is a change a pace especially when it is dealing with statistics, but I am glad to hear that it has developed your reading abilities on literature reviews.

I remember back in high school I had to write a literature review but my teacher did not really explain in to well. I do not really like reading but I realized that it is a very important part of college so now I am trying my best to read and write

Effort goes a long way for improvement!