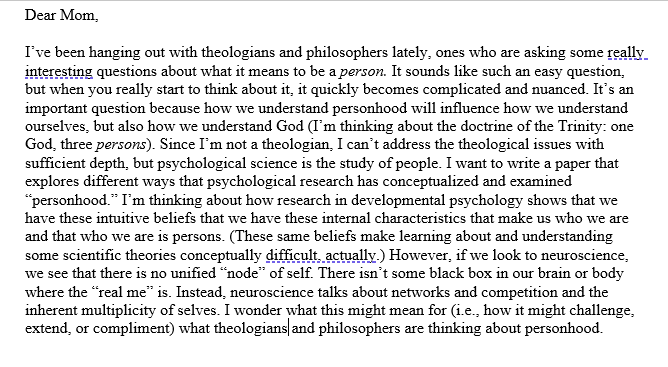

As I mentioned in the last blog, I often start writing a research paper/literature review with a dear mom draft. But a letter to my mother is not going to be accepted for publication (and is not likely going to fulfill the requirements of your class paper, either). So, we can’t stay with this draft for too long. (Though your mother is still welcome to read your final paper, even once you’ve deleted the salutation to her.) This is where my second tool comes in.

Tool #2: Organize Old School. Find a research paper or two that are closely aligned with your idea and start sketching (literally) the core features from this paper that might be useful to guide your search for other papers.

For the paper that I was writing on how psychology can influence theological thinking about personhood, I needed a good overview from psychology about persons. The problem is that psychologists don’t really use that word. We say “people” who have “self-concepts” and “personality dispositions” (and so forth). This in and of itself might be interesting to the primary audience of the paper (theologians and philosophers interested in how psychology might challenge, nuance, or advance discussions about personhood). But I knew I didn’t want to write a broad paper on all the different ways that we can define “self” in relation to “person” in psychology. (Someone else can write that paper.) Yet, to start to talk about a psychological view of persons, I would need an article that could give me a good overview of the area.

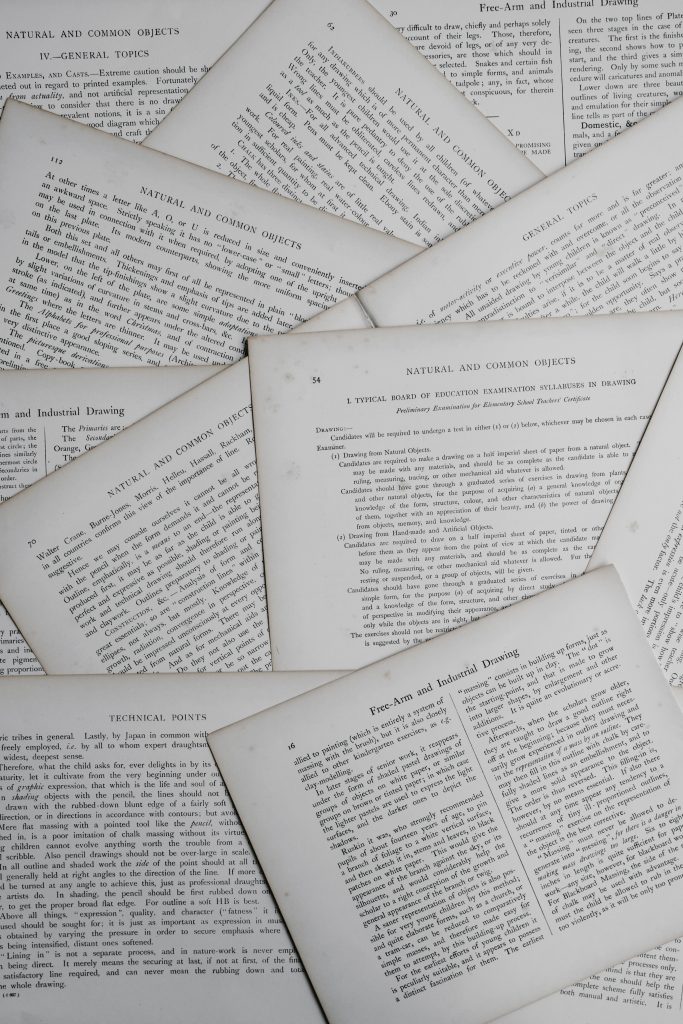

In psychology (and I suspect other disciplines, too), there are a number of “Handbooks” that are published as edited volumes, often with lengthy chapters written by different experts on important aspects of the topic or idea of the handbook1. These are often great places to start for in-depth (even if a bit dense) overviews on a variety of topics. When I stumbled upon the 2018 chapter by Sanaz Talaifar and William Swann on Self and Identity from the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology, I was thrilled. Although this chapter didn’t go into too much detail on any one topic within self and identity, it had the broad strokes (but scholarly) overview I needed to start to frame my ideas. And I did this old school style.

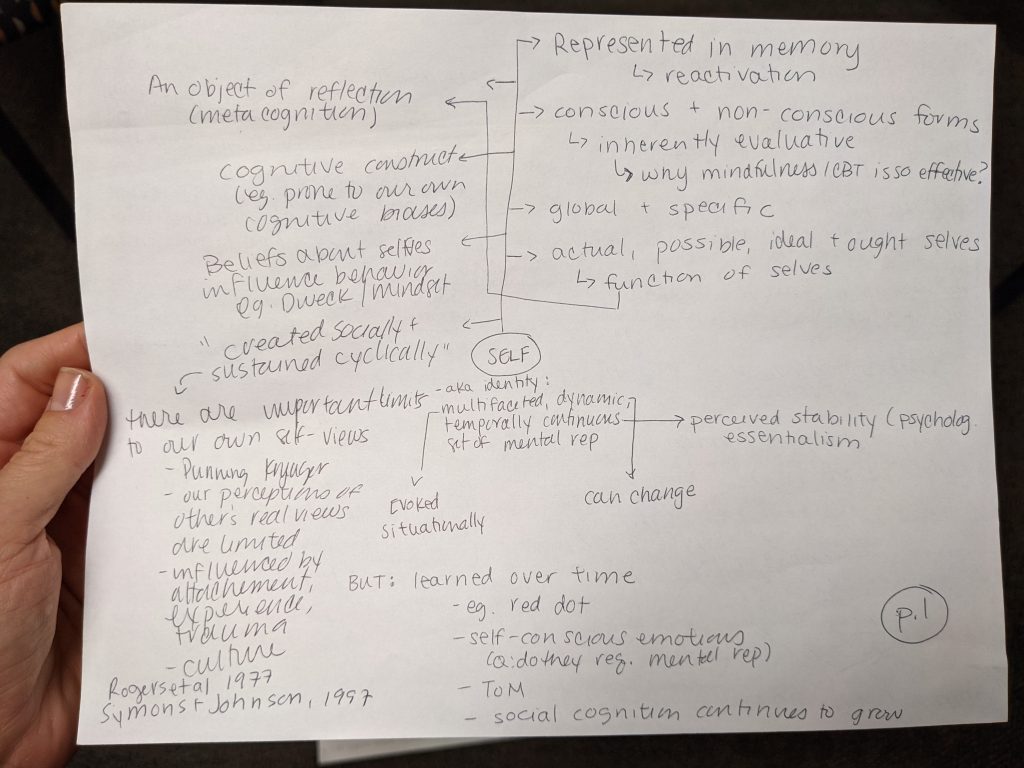

If you take a look at this page, you see that in the very center I wrote “self”. From there, I have a series of arrows highlighting different components of the self that Talaifar and Swann wrote about. You will also see I made a few notes (bottom left) with some additional references that I wanted to follow up on.

Although a lot of what is on this page is a truncated view of some of the ways of defining self-discussed in the chapter, but I also made notes of possible connections to consider exploring. For example, there are conscious and non-conscious forms of self and that these are inherently evaluative (see top right). This idea made me wonder whether mindfulness/cognitive-behavior theory is so effective because it can help individuals formalize the automatic, non-conscious, (presumably) negative evaluations of self that they engage2. In other places, I make connections to areas of my own expertise, such as the perceived stability of self, something attributed to “psychological essentialism” (from developmental psychology) or to Carol Dweck’s work on mindset (how what we believe about ourselves influences our behavior, which feeds back into our self-perceptions).

Basically, I find that by writing—with my hand, not on a computer—I have more flexibility to think and make connections. I can draw arrows, make columns, and try to identify crossovers. There is nothing magical about writing this out by hand—doing this old school—but I find it easier to spread the papers out across my desk and think when my hands have gone through the specific motions of writing than when I do the functional equivalent on the computer.

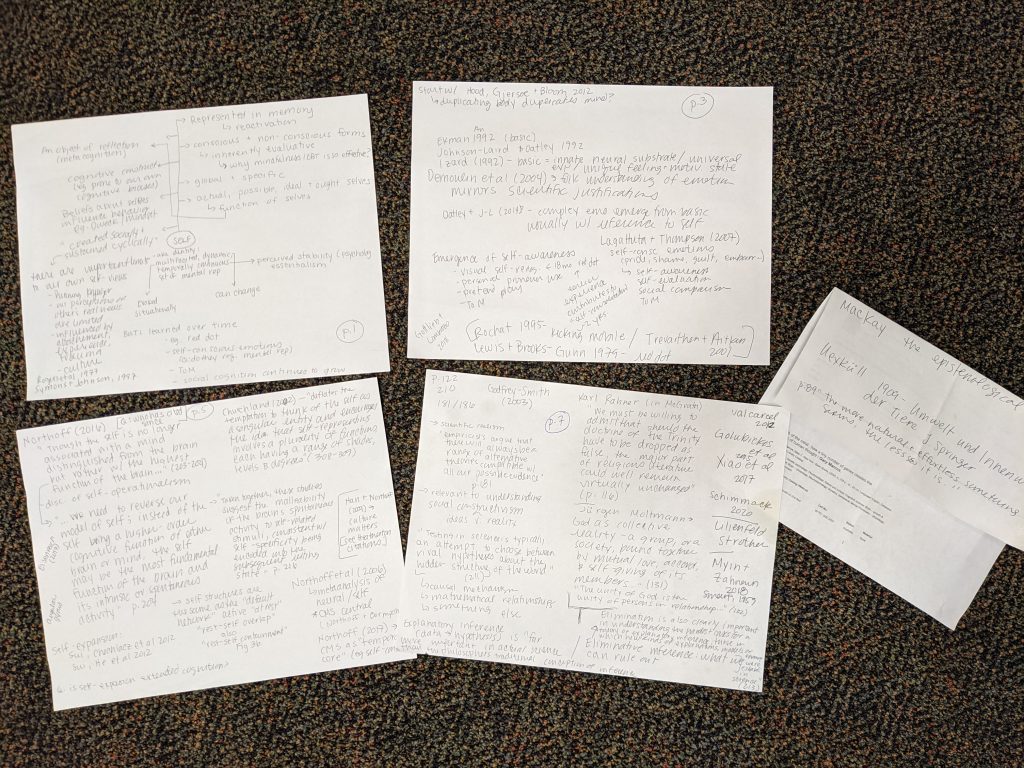

What you can see in this picture is the end result of my organizing. Each page is numbered and double-sided, flipping up from the long edge. I know this seems like a useless bit of trivia about my process, but I think it’s good to know that this is not how I usually write on paper; nor do I usually use unlined paper. This isn’t how I take notes. When I write on paper like this (this orientation, these columns, some arrows, lots of quotes, unlined paper…), it is a signal to me that I am moving from big ideas (dear mom) to how it might be accomplished (some core citations). These are notes that I take while reading articles on the topic (through database searches and by following promising citations that I read within interesting articles). These are not necessarily original ideas that I am generating, but instead interesting ideas from research papers/literature reviews that I am reading. My job as the author of a new paper is to bring these ideas together (the ones that remain relevant to my topic) in a way that opens dialogue for something new (a fresh view, a new idea, a reconsideration, an extended summary of this research).

I do this process until my ideas start to feel saturated. Saturation is a bit vague, but basically, I find that I have hit the point of saturation when I stop having new arrows/columns crop out of my notes. When my notes feel more like nuancing and extending specific ideas rather than introducing new concepts. Once I hit this point, usually 4-8 double-sided pages of notes like this, then I turn to a real, paragraph form draft. More on that in the next blog.

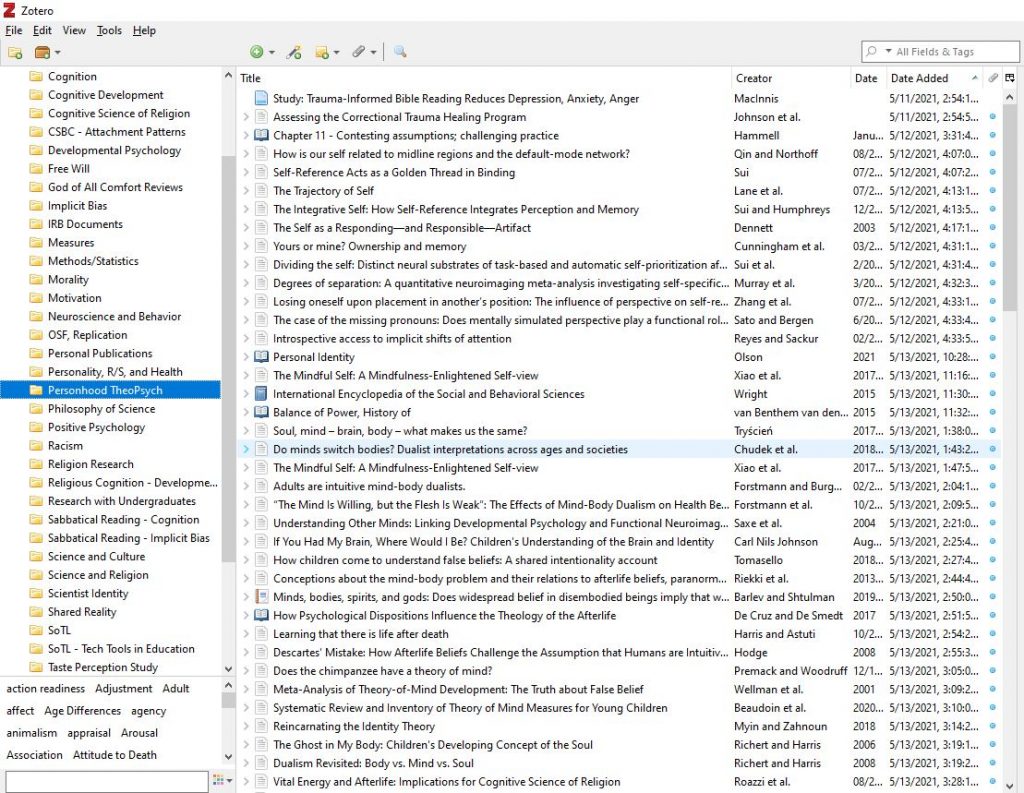

Also, a bonus tool: All along the way of this process, I’m saving papers into Zotero3. By the end of a 2-hour research session where I’m scribbling my notes and reading papers, I might have 45 tabs open (yes, I’m an active tab-opener). It is easy to lose track of where papers are across these tabs (much less the difficulty of finding them at a later date), so while I keep them open for reference in the moment, I also actively save them into a Zotero folder specifically labeled for this research paper project. You can see a snapshot of my “Personhood” paper Zotero folder here (along with a whole slew of other Zotero folders I have). Zotero, or some other reference management system, is like a researcher’s superpower. (I think Spiderman’s uncle was right: with great power comes great responsibility. In the context of research, I would say that with great power (of reference organization) comes great ideas.)

While you wait, I want to know: how do you organize your ideas and references?

_____________________________________________________

1For example, see a list of psychology handbooks published by the American Psychological Association and Cambridge University Press, though other publishers also produce high quality handbooks.

2That is, mindfulness can teach us to identify a thought in our head, but separate ourselves—literally our self—from that thought. I can have a thought, “I’m worthless” and I can evaluate that thought “hrm, I just had a thought that I’m worthless” without becoming that thought or accepting it as true “That was a thought I had, and it wasn’t true.” If you want to know more about this, in particular, I would recommend this book. Ignore the cheesy title and very self-helpy cover; it represents good scholarship and I have found the tools very helpful.

3Check out this CSHB resource page for more on Zotero and other tools for writing research papers.

If you found this blog helpful, check out the overview of the whole series here, so that you can find more useful information to develop your writing.