By E. Russ Bermejo, MSW, Lecturer

This is Part 1 of a 4-part blog post.

_____

We are designed for connection.

During the 2021-2022 academic year, our University Provost chose connection as the theme. I loved how Dr. Charles Sands continually reminded us to connect with others throughout the year.

This intention has forced me to think more deeply about how we are connected. I have a collection of Japanese kokeshi and Russian matryoshka dolls, which are wooden stacking or nesting dolls kept at each of my desks at home and campus. These heirloom pieces remind me how we are connected. They are a 3-D representation of “person-in-environment” (also known as PIE) a theoretical framework that underpins the social work profession. PIE is a practice-guiding principle that highlights the importance of understanding individuals and their behavior in light of the environmental contexts in which they exist (Kondrat, 2013).

It is quite easy to compartmentalize our lives or partition our thinking into artificially-created domains or silos. Where my mind wants to isolate or separate, and provide easy explanations to complex issues, these wooden dolls remind me to do otherwise. We are not mere objects, instead we have meaning defined by our interactions with our environment. We cannot see ourselves or anyone else outside of the world they exist in; or as essayist, Anaïs Nin wrote “We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.” Context always matters.

Seeing our world connected doesn’t sound earth-shattering, until you try to live it out intentionally. In practice, living connected is not easy.

How do we stay connected in a fragmented world? This was a question that I explored in my earlier blog post where I looked towards Japanese arts forms to show us the way towards meaningful integration. In these upcoming series of blog posts, I want to explore three questions:

- Blog #2: How do I live a life that is connected?

- Blog #3: How can my teaching be connected?

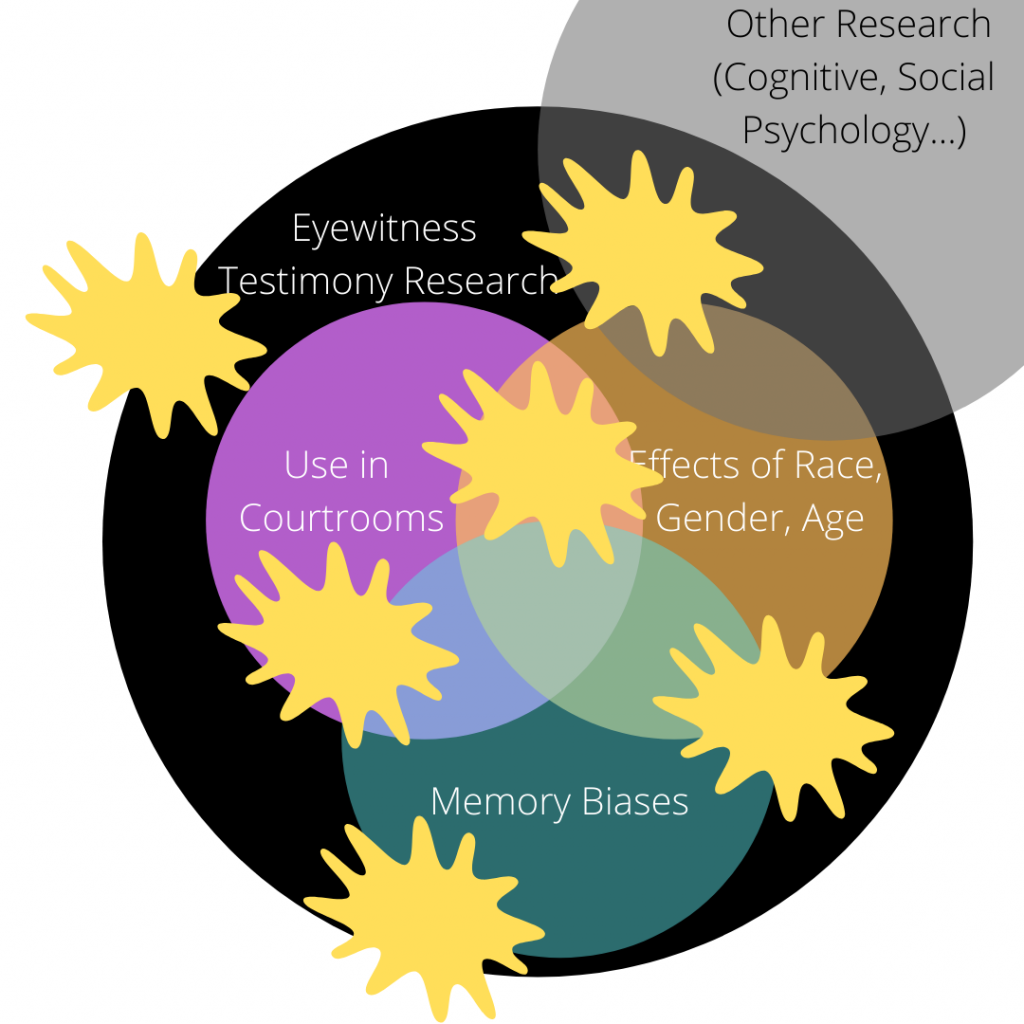

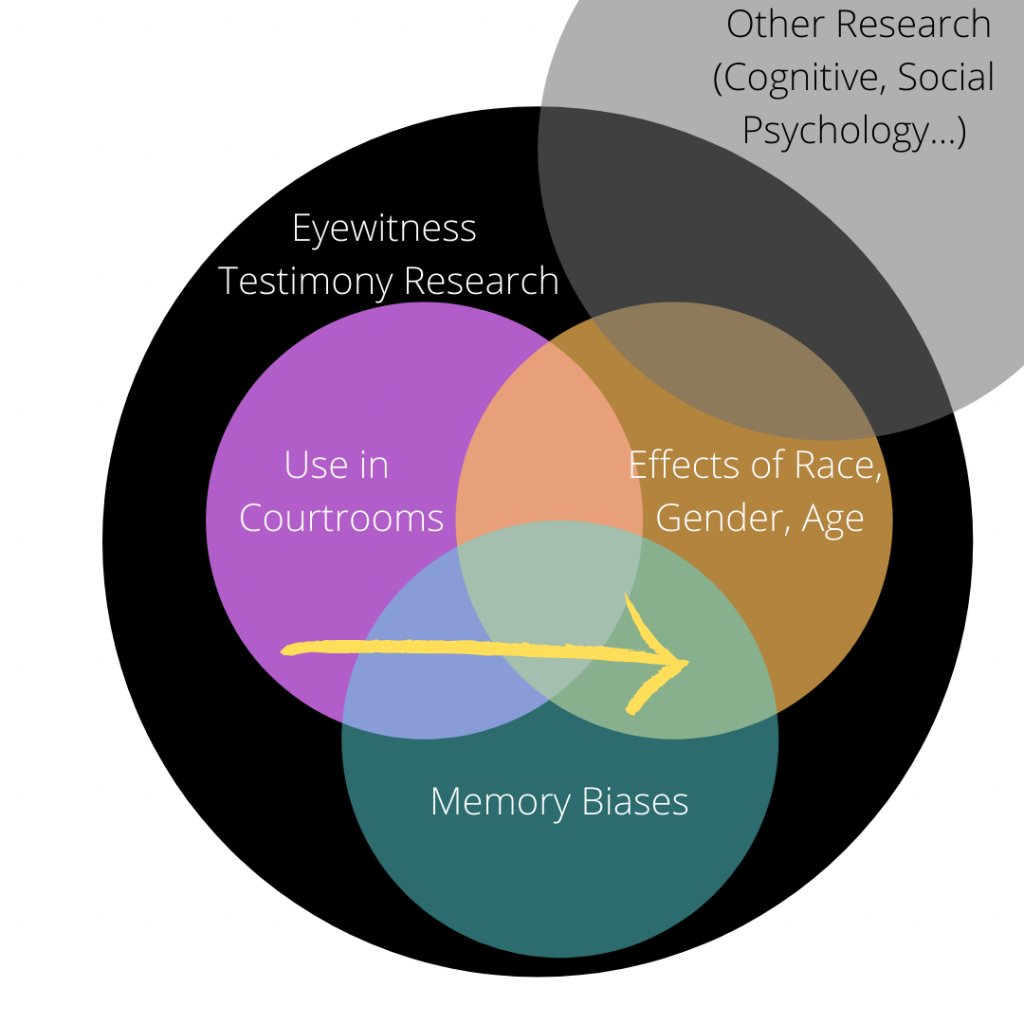

- Blog #4: How can our research be connected?

In each blog post, I will explore a key relationship to answer each of these questions, which, unsurprisingly, are all connected.

If you are faculty, I hope you find these blogs as invitations for brief and ongoing reflection and introspection, knowing that we show up more fully to our students when we show up fully to ourselves.

And if you are a student, I hope you will also accept the invitation to live a self-examined life1 (see Socrates) so you can discover life that is truly worth living (see Jesus). Although these posts were written primarily with faculty in mind, you are also on a journey here at CBU to discover a connected life of faith and scholarship. Together, we can live out our purpose, living a life of connection, courage, co-creation, and action. So, thank you for reading.

_________________________

1 The unexamined life is not worth living.”-Socrates