This is Part 1 of a 4-part blog series. Read Part 2 here , Part 3 here and Part 4 here.

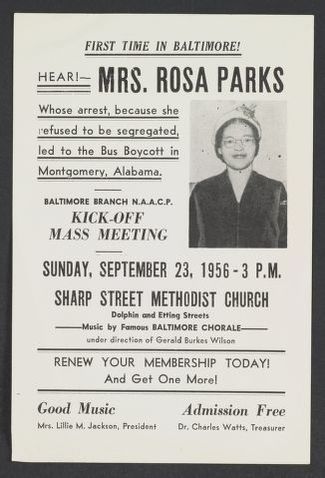

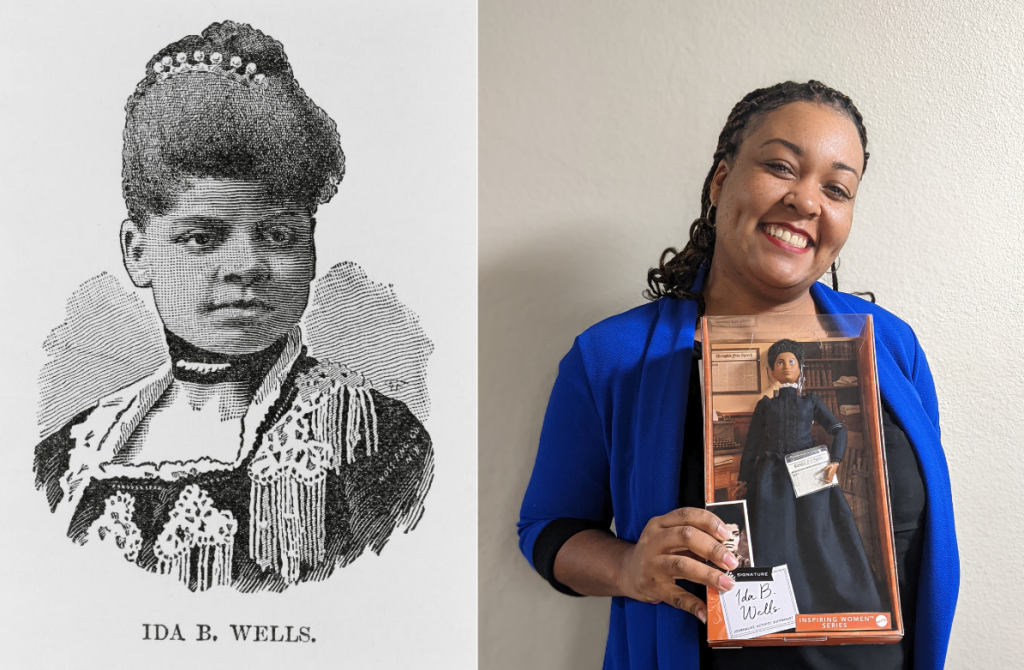

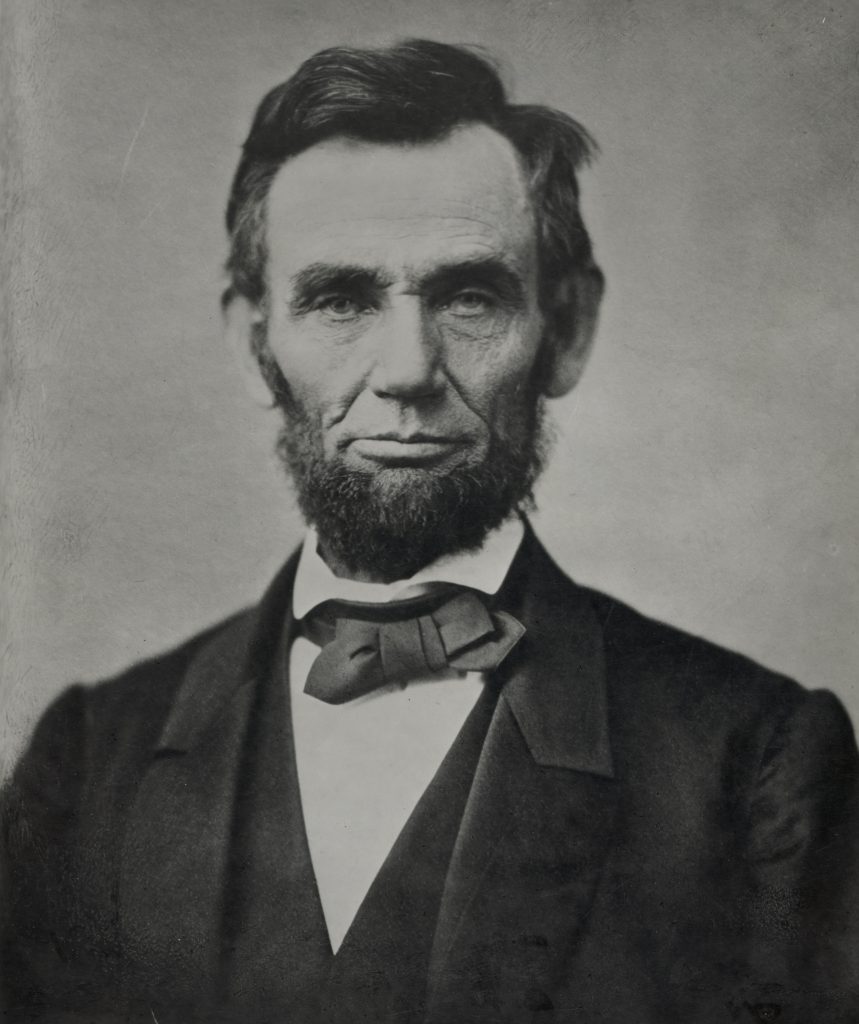

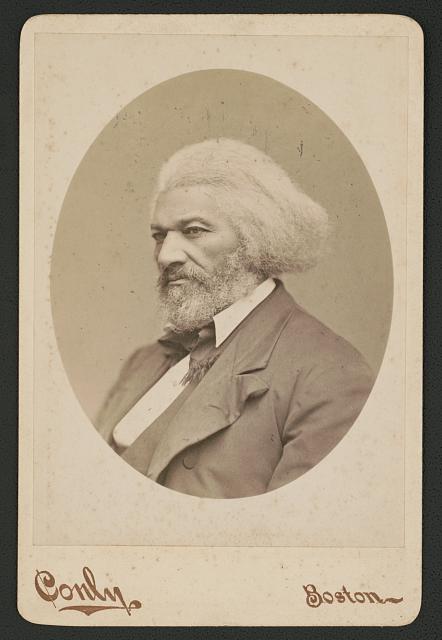

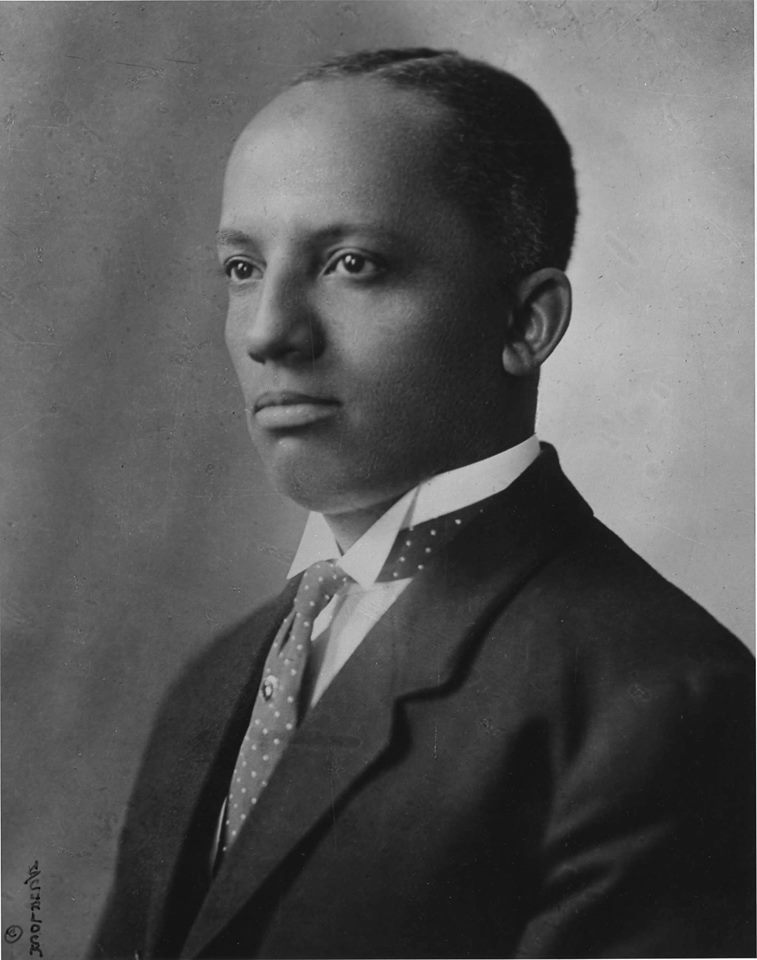

In 1926, Carter G. Woodson, known as the “Father of Black History”, launched “Negro History Week” to be observed annually every February in honor of the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809), and Frederick Douglass (estimated to be February 14, 1818, due to no official recordings of slave births). Carter G. Woodson stated, “If a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and in it stands in danger of being exterminated”. Negro History week, which later became Black History Month, was created by Woodson to encourage knowledge and interest in Black achievements and adversities while moving America to not simply focus on “Negro History, but on the Negro in History”. Woodson believed that appreciation of Black History would not only lift the confidence and esteem of African Americans, but enable African Americans to confidently, courageously, and comfortably engage in healthy conversations with White Americans, and other races, as equals in the advancement of humanity. In essence, the spirit of Black History Month is to enable all people to engage in healing conversations on race, that propel us towards a higher love and harmony amongst one another.

In the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, I and my colleagues were in a faculty meeting that was proceeding with business as usual. I remember the meeting concluding as I thought to myself “Are my white Christian colleagues really not going to say anything about the fact that another unarmed black man has been killed at the hands of law enforcement on video?” At the time, I had been working at CBU during the law enforcement murders of Greg Gunn, Philando Castille, Paul O’Neal, Terrence Crutcher, Jordan Edwards, Eurie Martin, Stephon Clark, Marcus David-Peters, Antwon Rose Jr., George Robinson, Botham Jean, Ronald Greene, Javier Ambler, Elijah McClain, Manuel Ellis, Breonna Taylor, Daniel Prude, and now George Floyd (we must say their names because their lives mattered), with these being the high profile cases that got news coverage, not including the 91 other documented murders of African Americans by law enforcement officers during this same period that received little to no attention. Nothing that we were discussing in that meeting seemed as important to me than the reminder the entire country had just witnessed through the camera phone of 17-year-old Darnella Frazier, that Black Lives Don’t Matter, and that I, my children, my family, my friends, my neighbors, or my students could be next. I, and my colleagues of color felt invisible in that meeting, unseen, unimportant, and insignificant, scarred by the silence of a Christian white majority that seemed to be disconnected from what we were all feeling on that day. In an angry outburst and tears, I expressed my feelings at the close of the meeting, presenting a scathing rebuke of the all too familiar silence of white Christians on social issues impacting people of color. I felt the words of Dr. King when he stated “There comes a time when silence is betrayal”; “He who accepts evil without protesting against it is really cooperating with it”; and “In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends”.

The hurt of that meeting led to some transformative hallway meetings in the James building of CBU, in which white and black colleagues engaged in healing conversations on race, which later led us to writing a book together, to help ourselves and others have cross-racial conversations that lead to healing, empathy, acceptance, and love, all in our collective pursuit of Christ and Christlikeness. In the process of these conversations, I discovered that my assumptions about the reasons for my white colleagues’ silence were wrong, and they learned that as their friend, I needed their voice and presence when tragedy strikes our community. The book that we have written as a result of these conversations is entitled: Healing Conversations on Race: Four Key Practices from Scripture and Psychology, is now available, and free copies of the book will be raffled to those who interact with our posts during Black History Month, in which I, and the three other authors of this amazing book, share thoughts, reflections, and suggestions based on the book, on how we can all have Healthy Conversations on Race.

The book uses the H-E-A-L acronym as a model to guide conversations on race. Each week during Black History Month, one of the letters of the acronym will be explained by one of the authors. For our first week, we will focus on “H” which is short for Humility in our model. I must confess, it was hard for me, as a black man, to begin any conversation with the suggestion that I needed to be more “humble” in a conversation on race. The collective black response to intergenerational, systemic, and historical oppression has been the model of humility, as we have sought to ingratiate, integrate, and imagine a better America while facing injustice, water hoses, unjust laws, de jure and de facto segregation, police dogs, lynchings, murders, rape, imprisonment, voter suppression, redlining, gerrymandering, invisible ceilings, medical experimentation, media stereotyping, microassaults and microinsults, and much more. Why should I, and those like me, be humble after enduring such domestic terrorism, provocation, and dehumanization? In the search for an answer to this question, I discovered an important truth, that we must grapple with in order to proceed. The call to have a healing conversation on race, cannot be motivated by the worthiness of the person with whom you will discourse, nor one’s personal feelings of being willing to engage. The call to healing conversations is not one that is led by an individual, but rather led by God, who reminds us that we, people of all races, are made in the Imago Dei (Image of God), and it is His desire that we “lower ourselves” to one another, just as He lowered His Son into our world, for our individual and collective salvation. If God could lower himself to be in skin, walk in the darkness of this world, be born into poverty, endure the nastiness of Roman oppression, be subject to wrongful imprisonment, police brutality, injustice in the court system, and ultimately murdered like George Floyd in the streets of Golgatha; who am I to say that I cannot embrace humility in conversations on race? While cultural humility is the lifelong process of reflecting, acknowledging, and critiquing one’s personal biases, what we propose in our book is a Christ-centered humility, which transcends cultural humility, because it moves us away from the adoption of the thoughts and trends of modern culture, and instead advances us towards a focus on Christ, as the perfect measure for understanding how we should engage with one another. In our gratitude for the grace extended to us from God, we humble ourselves before our brothers and sisters of different races, seeking to imitate our Savior, who came to heal the enmity between man and God; we humble ourselves to heal the racial tension that pervades our world. We are guided by the words of 2 Chronicles 7:14 “If my people, which are called by my name, shall humble themselves, and pray, and seek my face, and turn from their wicked ways; then will I hear from heaven, and will forgive their sin, and will heal their land.” We begin healing conversations with humility, understanding that when there has been a tear in a relationship, the most important thing is not to prove who’s right or wrong, but rather to move ourselves into a position where God can take control, and transform our opposition to another into an opportunity for us to grow closer together.

This Black History Month, I encourage everyone to consider engaging in healing conversations, focusing first, on Christ-Centered humility, responding not as the culture dictates, but rather adopting a Christlikeness, in which we lower ourselves so that God can initiate the healing process between us. In your celebration of Black History Month, in what ways can you adopt a Christ-centered humility to move you to be a better listener, encourager, supporter, and ally of someone of a different race? Your reflection on this question places a smile on the face of Carter G. Woodson and transforms Black History month from being a moment, into becoming a movement. Join us in the movement of promoting healing conversations on race.

This blog is the first of 4 in our Black History Month Blog Series for 2023. Check back each Wednesday of February for more on how to have healing conversations. CBU Students who comment on these blogs will have a chance to receive a copy of the book. Winners will be emailed in early March. Listen. Learn. Engage.

Read Part 2 here.

References

Goggin, Jacqueline (1997) Carter G. Woodson: A Life in Black History. LSU Press

Vazquez, V., Knabb, J., Lee-Johnson, C., & Hays, K. (2023). Healing conversations on race: Four key practices from Scripture and psychology. InterVarsity Press.