By Erin I. Smith, Ph.D.

Research.

Now that I’ve said the r-word, I want to acknowledge that you, my reader, may be having a particular physiological and psychological reaction. (Note that sweaty palms and racing hearts could be signs of anxiety or affection; my point here is just to note that you may be having a reaction.) Whatever your reaction is, I invite you to take some deep breaths and read on.

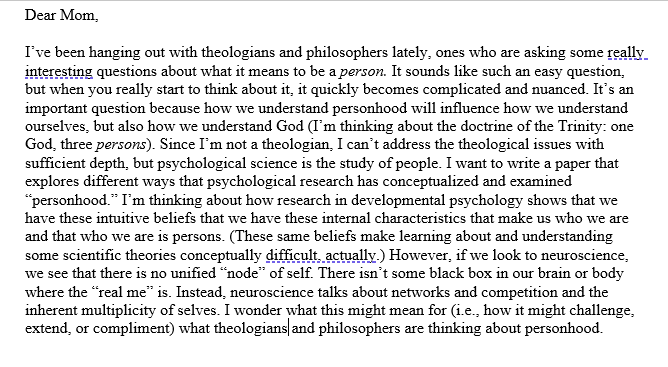

Research refers to a wide variety of practices aimed to systematically investigate questions in the pursuit of answers and (hopefully) understanding. These practices represent an important way of knowing in the world, an important tool to bring to addressing some of the most pressing questions in our culture. The idea that research is useful in knowing is not new. Many in church history (e.g., Justin Martyr, St. Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, John Wesley) highlighted how the Book of Nature can (and should!) be read alongside the Book of Scripture, as both reveal truth originating in God himself. Thus, for the Christian, reading the Book of Nature, as revealed through emerging research, alongside and through the lens of the Book of Scripture is not just an opportunity for a robust understanding of reality (though this is an important consequence), it affords significant opportunity to leverage ancient Biblical wisdom in the language of modern science for the glory of God’s name in our world.

For me, this is an essential starting point for any conversation about research, especially research at California Baptist University, a distinctly Christian University committed to the Great Commission. Because I believe that the gospel—the good news of Jesus Christ’s death and resurrection—is world changing, I am committed to using all tools provided to me by God to share this news. As the Apostle Paul writes to the Corinthians, “…I have become all things to all people so that by all possible means I might save some. I do this for the sake of the gospel, that I may share in its blessings.” (1 Cor. 9:22-23). Although research symbols like the beakers found in a modern chemistry lab would not exist for nearly two millennia after Paul’s letter, I think that today Paul might include speaking the language of science and research in his exhortation if opening the Book of Nature would provide a means to engage and share the Book of Scripture.

Although I could say more about the importance and rationale of engaging science faithfully as Christians (and I have, in small part, in this publication), I want to move from general statements about “Christians engaging research” to specific statements about the culture of research at California Baptist University.

For faculty who have been around CBU for a while, it will not be surprising that a culture of research is a consistent priority. To this end, in 2019, the University celebrated and dedicated a momentous achievement: the announcement of a new endowed professorship, the Fletcher Jones Endowed Professor of Research. In October 2021, I had the honor of being appointed into this professorship. However, it’s important to note that what makes this endowed professorship particularly unique is that rather than being a role to support a single person’s research agenda, this role is dedicated to the elevation and support of faculty research across CBU’s many schools and colleges. In other words, I have the distinct privilege of supporting, equipping, and elevating the incredible and diverse research that is ongoing and developing at CBU. This is truly a privilege given what I’ve already said about research: that it can be a God-given tool to address critical issues in our community and world for the glory of God’s name and kingdom.

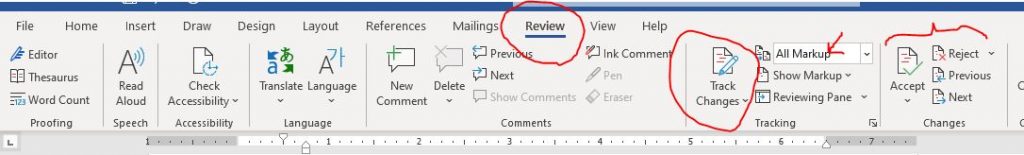

I share this with you as a preamble to an invitation for you. In my role, one of my primary goals is to help CBU faculty develop, conduct, and finish research more successfully. This is not just about lines on vitas, nor is this in competition with our steadfast commitment to delivering excellent educational experiences for students. This is about leaning into our God-given calling and unique position at California Baptist University to engage research in a way that enhances our educational mission and speaks God’s truth into complex problems. For me to support you in this journey, I need to hear from you. What kinds of research do you do? What do you feel called to do? What are your barriers to engaging research? What kinds of supports do you need? This is my first invitation to you. I have set up several small group conversations for me to ask these questions so that I might hear from you, the researchers I aim to support, as to how I might best support you. I would love to listen and learn of your experiences, hesitations, victories, and challenges in research, and ideas you might have to help you thrive in this capacity. Please consider signing up here to participate in the spring, 2022 semester.

A second, but related invitation, is to participate in a faculty learning community I am leading in the spring 2022 semester. Across 6 meetings, we will meet to discuss Robert S. Tyan and Avidan Milevsky’s (2016) text Launching a Successful Research Program at a Teaching University. I am offering this group twice, in hopes that one of the times might work in your schedule. This is a great opportunity for individuals who are looking to get started to wade into the research waters alongside others looking to do the same. This learning community aims to help participants identify common barriers to engaging research at teaching institutions like CBU and equip them with tools and resources to overcome these barriers. I would encourage you to make time for this. You can sign up here.

If any of this has piqued your interest, I would encourage you to sign up for these opportunities, to follow up with me, and to start a conversation. We are all in different places—and that’s okay! I hope that in the coming months and years, I will have the privilege of meeting you wherever you are to support and extend the research that God has entrusted you with. I look forward to hearing from you.