Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) has become increasingly controversial, sparking intense emotion and debate. DEI in education, business, and industry have captured recent headlines due to school board protests and questions about “DEI hires” in industry. Along with DEI, racism, diversity, “wokeness” and critical race theory (CRT) are terms that garner immediate, visceral responses when uttered. The Brookings Institute (2021) assessed legislation related to CRT and found that nine states have passed legislation to ban discussing the belief that racism is embedded in United States institutions and society. Only two of the nine states explicitly mention CRT in their legislation, but all prohibit discussing the US history of racism. “Nearly 20 additional states have introduced or plan to introduce similar legislation” (Ray & Gibbons, 2021).

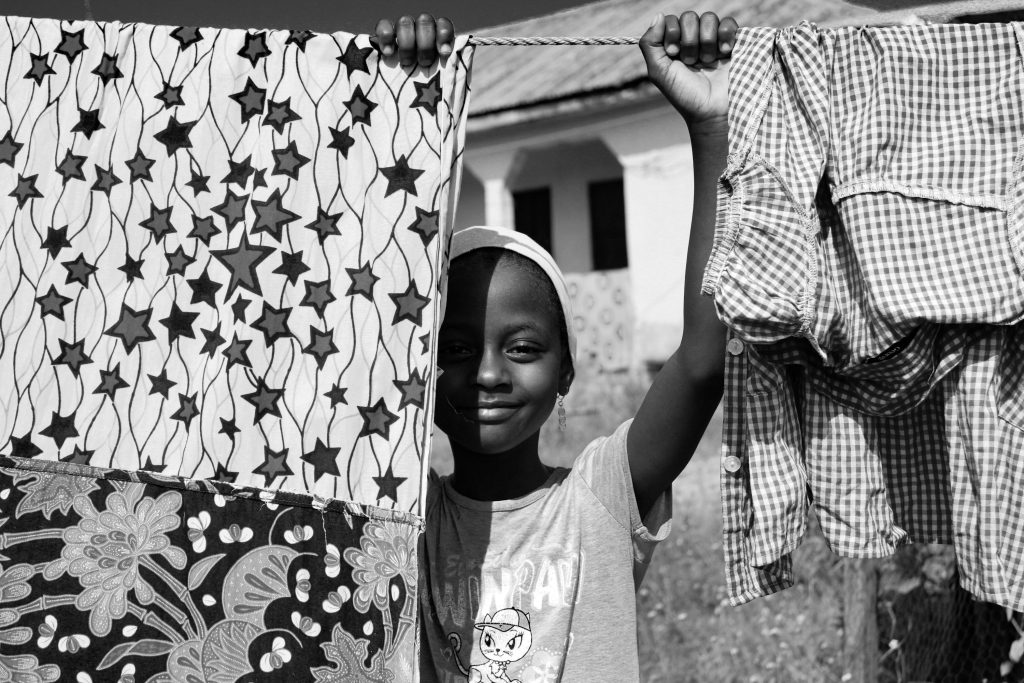

My interest in race equity is driven by my own family and community history of racism and discrimination in education, business, and social interaction. What does that mean? My maternal and paternal family moved to Los Angeles from the farms they worked in the South during the Jim Crow era. They all made their way to Los Angeles in the 1940s during the Great Migration pursuing better opportunities. They left poverty and disenfranchisement in pursuit of opportunities to vote, be educated, and own property. During the reconstruction and Jim Crow eras, Black people were barred from acquiring wealth. According to (Inequality.org, 2025),

If average black family wealth continues to grow at the same pace it has over the past three decades, it would take black families 228 years to amass the same amount of wealth white families have today.

That’s just 17 years shorter than the 245-year span of slavery in this country. For the average Latino family, it would take 84 years to amass the same amount of wealth White families have today—that’s the year 2097.

I pursued social work out of concern for the wellbeing of marginalized groups that have limited access to resources for various reasons. My research is focused on the social problem of African American overrepresentation in the child welfare system. I am sometimes asked why I focus on African American children and families. I often feel compelled to justify that African American overrepresentation is a legitimate issue due to the assumption that focusing on one group neglects the needs of other groups.

Scholars have documented the relationship between poverty and substandard housing in resource-poor communities and African American dependence on social welfare systems (Hill, 2004). Overexposure to social welfare systems coincided with the enactment of the Child Abuse Protection and Treatment Act (CAPTA) of 1974 to promote child removals aimed at rescuing poor Black children from the conditions in their families (A. J. Dettlaff & Boyd, 2020; Roberts, 2020, 2021b; Smith Brice, 2019).

African American overrepresentation in the child welfare system has existed for over 60 years (Giovanonni & Billingsley, 1972). When discussing the need to for equity work, it is vital to start with the data. As of 2021, African American children represent nearly 14% of the USA’s general child population and 23% of the USA child welfare population.

In 2022, I conducted a scoping literature review to determine what was known about efforts to eliminate African American overrepresentation in child welfare. My review was limited to efforts (e.g. programs, strategies, and interventions) focused specifically on eliminating African American overrepresentation. Since many child welfare overrepresentation efforts are focused on children of color, my focus on African Americans significantly reduced the amount of literature available – from 510 to 42. My scoping review identified 42 specific efforts at the macro, micro, and mezzo levels of social work practice. I then analyzed the impact of each of the 42 efforts. Of the 42 efforts, I selected one race equity effort to study further for my doctoral comprehensive project.

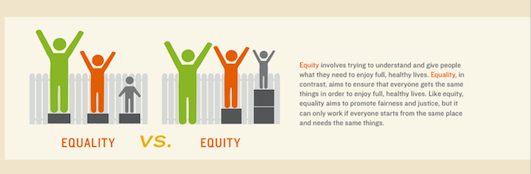

According to the Colorado Office of Health Equity (2023) equity exists “when everyone, regardless of who they are or where they come from, has the opportunity to thrive. This requires eliminating barriers like poverty and repairing injustices in systems such as education, health, criminal justice and transportation.” Equity efforts do not seek equality because equity assumes that not all people groups start at the same level. Equity efforts acknowledge social stratification and aim to eliminate systematic and institutional barriers.

My doctoral comprehensive project was a formative evaluation of the implementation of the Race Equity Strategy Areas (RESA) developed by The Black Administrators in Child Welfare (BACW). BACW is an organization focused on addressing the disproportionality of African American children and families in the child welfare system. BACW’s leaders are often asked why they focus specifically on African Americans as opposed children and families of all races and ethnicities. BACW published 10 RESAs in 2011 to fill a gap in the field of Child Welfare relative to race equity. RESA moves beyond conversations about culture and bias to achieving Race Equity. The child welfare system was not designed for Black children and families, and the outcomes reflect its racist origins and practices. (Gourdine, 2019; McDaniel et al., 2021)

In light of the current administration’s rollbacks on DEI work , I am monitoring the impact on the equity work that I do. There is still a need to transform the systems that serve the people Jesus referred to as the “least of these” in Matthew 25:40. Christ taught and demonstrated compassion and action on behalf of marginalized people and children (Bible NKJV, Matthew 25:37-40, Matthew 19:13-15, 1982). According to Ulmer (2019),“Black theology grew out of the marginalization of African Americans” (p. 57). Ulmer further describes black theology as addressing the “cultural, sociological position of African Americans [which] emerged from the state-sanctioned marginality of their culture” (Ulmer, 2019, p. 59). In my faith and in my work and research, I live in the tension of seeing social problems and attempting to address them as Christ would. How does your faith impact your view of social problems? What is your view of “the least of these”? Who are they, and how does that impact your studies and your work? As a follow-up to this and my previous blogs, I’ll revisit my scoping literature review on the overrepresentation of African American children in child welfare. I look forward to sharing what I learn in part 2 of this blog.

References

Bible NKJV. (1982). New King James Version Holy Bible (Inc. Thomas Nelson, Ed.). Thomas Nelson, Inc.

Dettlaff, A. J., & Boyd, R. (2020). Racial Disproportionality and Disparities in the Child Welfare System: Why Do They Exist, and What Can Be Done to Address Them? Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 692(1), 253–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716220980329

Giovanonni, J., & Billingsley, A. (1972). Children of the Storm Black Children and White Child Welfare.

Gourdine, R. M. (2019). We Treat Everybody the Same: Race Equity in Child Welfare. Social Work in Public Health, 34(1), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2018.1562400

Hill, R. B. (2004). Institutional Racism in Child Welfare. Race and Society, 7(1), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.racsoc.2004.11.004

Inequality.org. (2025, January). Racial Economic Inequality – Inequality.org.

McDaniel, S. L., Destin, Y., & Dyer, E. (2021). Using Critical Race Theory to Address Outcome Disparities in Child Welfare.

Ray, R., & Gibbons, A. (2021, November). Why Are States Banning Critical Race Theory_. Https://Www.Brookings.Edu/Articles/Why-Are-States-Banning-Critical-Race-Theory/.

Roberts, D. (2020). Abolishing Policing Also Means Abolishing Family Regulation n. https://imprintnews.org/child-welfare-2/abolishing-policing-also-means-abolishing-family-regulation/44480?gclid=Cj0KCQjwzqSWBhDPARIsAK38LY_r5_wXjx

Roberts, D. (2021). Racial Justice in the Child Welfare System Transcript.

Smith Brice, T. (2019). Reconciliation Reconsidered: Advancing the National Conversation on Race among Christian Social Workers. Social Work & Christianity, 46(2), 8–20. https://doi.org/10.34043/swc.v46i2.74

Ulmer, K. C. (2019). Walls Can Fall. Carver House Publishing.