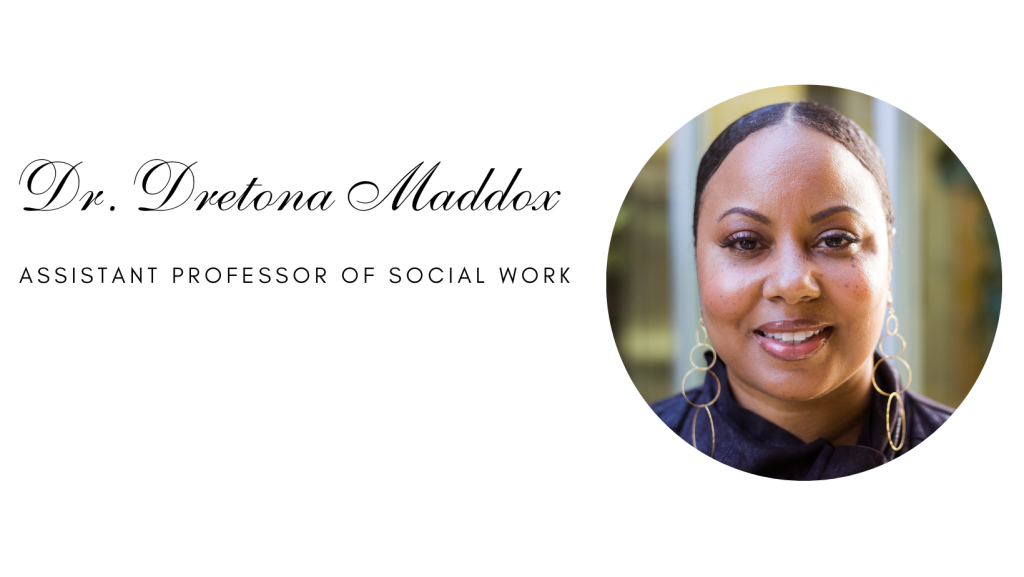

Each semester, the CSHB offers events to develop and empower researchers (students and faculty alike!). Last semester, we had the honor of hosting Dr. Sarah Schnitker, who presented her research and a workshop on tips for succeeding in research. Details about these events, including recordings and slides for her research presentation, are available in the Events tab. Below, the CSHB Student Worker shares her take on one of these events. You’ll see from her reflections that attending and engaging was worth her time. I wanted to share her reflections now because, in a few weeks, we will be hosting our spring speaker, who will present on engaging in multidisciplinary research. You can find details about this presentation on the Events tab. Read on, and I hope to see you on February 9th at our next event!

– Dr. Smith, Director of the Center for the Study of Human Behavior

How to Succeed In Research

Most people have specific interests of some sort, whether that be in education, social systems, art, science or any domain of life. Personal goals and topic focus may vary between individuals, but the innate desire to search for solutions to tough questions, probe the unknown, and make a positive contribution to the world serves as a unifying element in becoming…. a researcher. The word research on its own might be enough to instill anxiety or maybe even a sense of impossibility. Stressful emotions will be inevitable at times, especially throughout pursuing higher education or while learning new skills—like conducting research.

However, many students, including myself, might experience a prolonged intellectual roadblock as a result of these emotions, a roadblock that encourages the avoidance of research rather than a courageous engagement with research. My prayer this year is to ask God for a humble heart that is courageous but not proud, one in which fear does not stagnate my motivation. The quest and goal for myself as an undergraduate psychology student is to press into all the feelings- the good, the bad, and the ugly.

“Courage is resistance to fear, mastery of fear — not absence of fear.”

Mark Twain

Dr. Schnitker of Baylor University presented three tools that can be used to combat the fear of failure, anxiety, and remaining stagnant in the pursuit of research. She highlighted the epistemic value of learning how to manage rejection well, implement intentions, and evaluate social networks which all have a role in the development of becoming a more successful researcher. And trust me, she knows a thing or two about being a successful researcher! Her workshop emphasizes a highly inclusive and practical approach to help evaluate common research habits that could lead to intellectual roadblocks such as anxiety or procrastination. Dr. Schnitker carefully pointed out that these skills do not always guarantee a desired outcome, but they will orient the developing researcher in a way that is healthy and, ultimately, more productive.

#1 Using Rejection and Failure as Motivation

So, what was the first thing Dr. Schnitker mentioned as a tip to succeed in research? The learned skill of using rejection and failure as a tool for motivation. Throughout her career, Dr. Schnitker has procured more than ten million dollars in grant funding and has been successfully published in multiple academic journals. To some, this may seem unattainable or beyond their intellectual caliber, but she asserts that persistence and normalization of rejection are aspects among many that contribute to these success rates and endowments. She fosters the idea of finding value in rejection and advocates for a shift from viewing it as a failure to a proactive moldable approach across a wide range of intellectual capacities. The primary difference between a scholar who has received a lot of grant funding or published a lot of papers and one who has not, according to Dr. Schnitker, is that the former has submitted a lot more applications (and thus received more rejections and failures).

As an unhealthy perfectionist at times, I resonated with this tip. At times I have become so worried and fearful of rejection that I essentially rob myself of the opportunity to even fail at all. The absence of opportunities to fail then develops a proxy that inhibits opportunity for growth. As an undergraduate senior psychology student, I am learning how to rest better in certain losses knowing that God can turn them into wins. The painful emotions that can become embodied after academic or personal life rejection are heavy, but despite this we see the Psalmist declare “It was good for me to be afflicted, that I might learn your statutes”- Psalm 119:71

“Multiple rejections do not indicate poor product or low competency”

Dr. Sarah Schnitker

#2 Mental Contrasting and Implementation Intentions

The second tip stemmed from research done on mental contrasting and setting implementation intentions (Duckworth et al., 2011). The focus here is to automatize the pursuit of goals which can prove to be useful in combating negative emotions such as stress and anxiety that may accompany research and deadlines. The first step is to engage in mental contrasting by conceptualizing a large-scale goal such as choosing a research topic focus for graduate school or maybe completing and defending a dissertation. Next, assess what factors might be preventing your pursuit or completion of the goal, as this will encourage active movement instead of passive dwelling. Implementation intentions should be framed in an “if-then” form to provide flexibility and accommodation. For example, if I need more time to work on a project, I could set up an intention that says, “If one of my classes is canceled, I will use that time to work on my research paper.” In addition to the time I have “regularly scheduled” to work on this project, I have pre-decided what to do with any extra time that I might receive unexpectedly (e.g., a canceled class) so that I am prepared to act (rather than wasting the extra hour deliberating what I should do with the time).

This process could be visually conceptualized as the materials needed to complete a piece of art. The intentions are the various tools such as paintbrushes, sponges, or clay and the work of art here is the goal identified during mental contrasting that is completed. This method is useful for established researchers but also gives undergraduate students a tangible way to track beginning goals and see if they come to fruition, whether that be in a career or graduate school.

#3 Prosocial Mentoring and Networking

Research excels as a collective team science approach in producing impactful data and providing implications for a wide range of scientific subfields. This kind of research is possible when a researcher has a sufficiently robust social network, a network that can play a crucial role in the development of strong, diverse research skills.

The National Center for Faculty Development & Diversity Mentoring Map (NCFDD) is a tool available online that can be used to assess personal and academic networks. Although it says “faculty,” this resource is relevant beyond faculty members and scholars. Dr. Schnitker discussed how this map can help promote self-awareness regarding individual access to opportunities, mentors, professional development, and emotional support, highlighting strengths and weaknesses in a social network. Assessing your strengths and weaknesses involves identifying and accepting where you are now. This supports the realization that networking opportunities extend into wide categories. For example, if you are lacking in access to opportunities from internal mentors the map points towards another area to explore, such as peer or external mentors. This map encompasses a prosocial system view ideally built on moral good, virtue development, and generosity.

Who are the people in your life watering your intellectual desires and goals? How can you foster a system of intellectual giving with virtues such as selflessness, humility, and patience? Proverbs 27:17 states “Iron sharpens iron, as one man sharpens another.” As Christians in the behavioral sciences, we can joyfully take on the responsibility of intellectually sharpening our peers, students, and humanity. Amidst the unknowns and hardships that naturally occur in life and within research, we can rest in the truth that God is not of confusion but of peace, and is faithful to complete the good works he began. (1 Corinthians 14:33, Philippians 1:6)

“Many things are possible for the person who has hope. Even more is possible for the person who has faith. And still more is possible for the person who knows how to love. But everything is possible for the person who practices all three virtues.”

Brother Lawrence

Call To Action!

Considering Dr. Schnitker’s three tips, my invitation to you is to identify areas where you may start to implement them. What areas can you identify in your educational endeavors that could use some polishing? Although we all have different starting points and come to the research playing field with different innate skills, the struggle with fear and perfectionism combined with the need for support is nearly universal. It is in these struggles that I encourage you to combat the negative perceptions of failure, implement goals, and seek out networks that strive to support you with integrity. The significance of social support is clear as humanity does in fact flourish in social contexts, but I also encourage you to not neglect the deep-seated value within yourself. The NCFDD map highlights this value as the “Accountability For What REALLY Matters” component stems back to yourself. The word “accountability” caught my attention, and although sometimes synonymously used with “responsibility” their applications can be distinct. Responsibility is important, but it embodies a stronger consequential focus on the duty to complete rather than giving an account for actions already completed. A challenge for yourself then is to press into this accountability for potential failures or past mistakes and use them as motivation to set goals and seek out networks, all of which will help you in becoming a more well-rounded researcher!

Photo by Zen Chung

References

Duckworth, A. L., Grant, H., Loew, B., Oettingen, G., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2011). Self‐Regulation strategies improve Self‐discipline in adolescents: Benefits of mental contrasting and implementation intentions. Educational Psychology, 31(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2010.506003

McGrath, A. (2014, September 15). Big picture or big gaps? why natural theology is better than intelligent design – article. BioLogos.