By Dr. Erin Smith

Are you familiar with Jesus’ parables in Matthew 13? The ones about the seeds falling in rocky soil, thorns, or good soil? Or about sowing weeds among seeds, or the size of a mustard seed plant? Among these verses, as Jesus explains why he speaks in parables, he says, “But blessed are your eyes because they see, and your ears because they hear. For truly I tell you, many prophets and righteous people longed to see what you see but did not see it, and to hear what you hear but did not hear it.” (Matthew 13: 16-17).

Why was it so hard for the religious leaders to open their ears and eyes? (And, related, why is it so easy for us to see that their ears are closed, but be blind to areas of our own deafness? See Matthew 7:3-5 if you don’t believe that we are blind in this way.)

As a psychologist, I think about this question in empirical—testable, measurable—terms. And it turns out that psychology has been investigating a variant of this question for the past 5 or 6 decades. When the question of hearing ears and seeing eyes is rephrased in psychological language, it might look something like this: how are incorrect beliefs revised; how are beliefs challenged and changed in such a way that we move closer to truth, and why do we so rarely see legitimate belief change in light of evidence? I think this is a fair rephrasing of Jesus’ question because Jesus wasn’t saying, “blessed are you because you’ve always believed the right thing”, but rather, blessed are you because you remained open to—and were thus changed by—God’s truth, despite the fact that it wasn’t what you were originally thinking, expecting, or looking for.

The story that psychological research tells about belief revision, about the process of opening our ears and eyes, is nuanced. It turns out that the cognitive and social systems humans are equipped with and embedded in have particular operations that make belief revision especially difficult. Much of this nuance is explored in an area of psychology called motivated reasoning (see Kunda, 1990) or, more recently, in the study of cultural cognition. Although we might hope that the goal of human reasoning is accuracy (e.g., moving closer toward what is true, in reality), research in psychology shows that we all also engage in forms of motivated directional reasoning. Motivated reasoning refers to the process of evaluating arguments and evidence in such a way that we arrive at our preferred conclusion. That is, we engage with information in a way that allows us to preserve our beliefs, even in the face of data to the contrary. Maintenance of beliefs may be another goal of human reasoning, a goal that is sometimes at odds with the goal of accuracy.

A considerable amount of research on motivated reasoning is nested within the context of politically-motivated reasoning (though religion is also an important factor that must be considered). For example, Campbell and Kay (2014) demonstrated that motivated reasoning is due, in part, to an aversion to the solution implicated in the problem. If we don’t like the solution, we are motivated to dismiss the problem (i.e., claiming that the data do not actually show a problem, that the problem is overstated, etc.). Crucially, Campbell and Kay demonstrated the explanatory power of solution aversion for Republicans and Democrats, albeit for different issues. Republicans and Democrats both dismissed issues when they were tied with solutions that countered typical conservative or liberal ideals.

Potentially more powerful in promoting motivated reasoning than solution aversion, however, is the connection of our beliefs to our identities. Shared Reality Theory proposes that “experience is established as valid and reliable to the extent that it is shared with others” (Hardin & Higgins, 1996, p. 28). That is, when we share beliefs with others, not only does that bond us with the other, but it also provides “evidence” of the reality of that belief. For example, research suggests that individuals were less likely to accept scientific arguments if they believed that their parents or friends did not accept those same arguments; accepting the argument would have threatened the reality shared within these relationships.

To be clear, motivated reasoning is rarely (if ever) conscious. People rarely look at data, read articles, have a debate with a friend and think, “I’m going to take what they say and totally misinterpret it…on purpose!” No, that’s not what happens. Rather, as a function of unconscious cognitive processes, we selectively remember, interpret, are critical of information in a way that protects our beliefs. If the evidence can be discounted (for presumably “good” reasons), then our beliefs can continue unchanged and the social connections with whom we share these beliefs are maintained or even strengthened.

Think about the implications of this. When evidence comes to light that something that we believe might not be true, it’s not just about the data. In fact, research in motivated reasoning indicates that exposure to data that suggests we might be wrong may, in some cases, polarizes belief, causing us to believe more strongly despite the mounting evidence that the belief is wrong. Why is this? Our most important beliefs are inextricably intertwined with our most important social connections. Shared Reality Theory suggests that these relationships are important, in part, because of their connection to the beliefs shared within them; our relationships validate our beliefs and our shared beliefs solidify and strengthen our relationships. (It’s a bit of a chicken-egg/important belief-important relationship thing.) Considered in this light, changing beliefs also threatens to upend our most pivotal social connections and our understanding of what makes life meaningful. What shared reality suggests is that it is exceptionally difficult to change beliefs, especially some of our most important ones, because of the threat this change implies for our social world. This is true even when there is a lot of evidence that our beliefs are wrong.

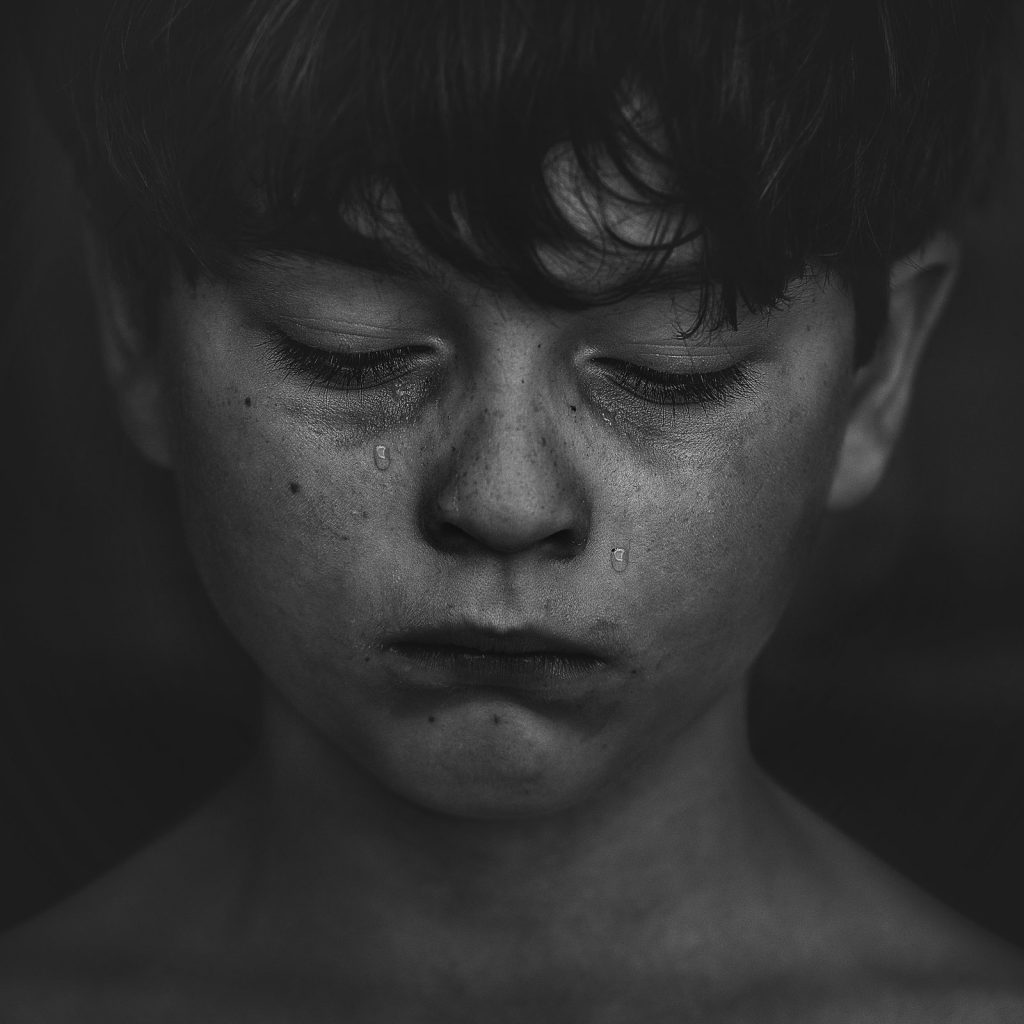

Photo by Mohammad Metri on Unsplash

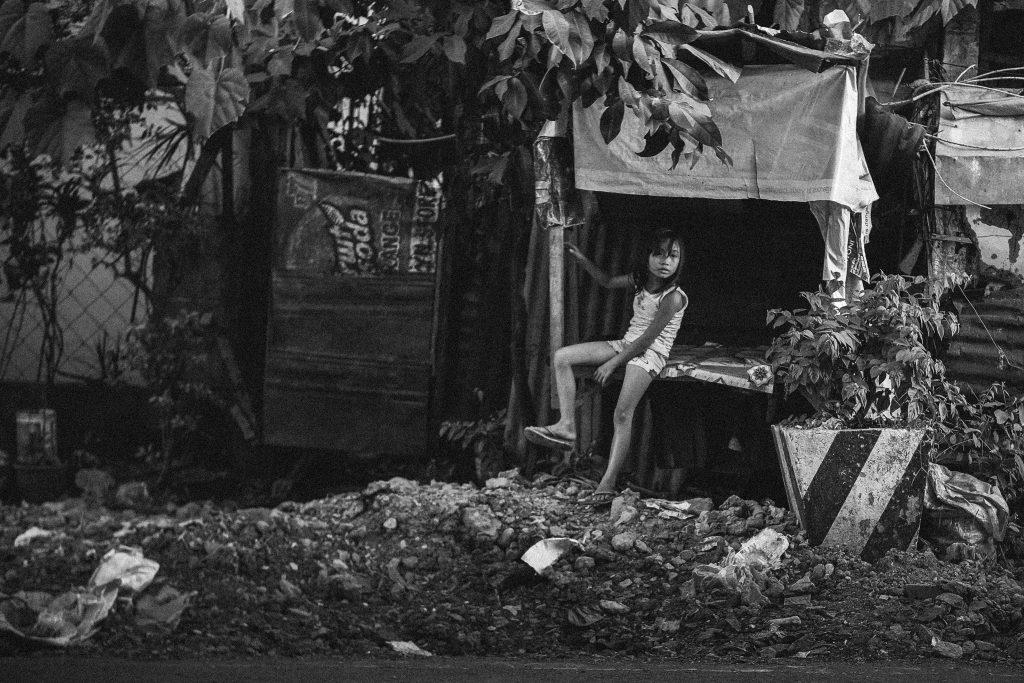

Photo by Erika Fletcher on Unsplash

At this point, let’s return to the original question of the blog: why was it so hard for the religious leaders to open their ears and eyes? We find one answer in the very human process of motivated reasoning, especially considering the power of our social relationships as both a source of belief validation and belief maintenance. Although it might be easy for us to paint these religious leaders as bull-headed, arrogant, or even just as unidimensional characters in a story, this would be a mistake. These religious leaders were challenged with information that contradicted their views—their views about religion, who the Savior would be, what the Messiah would do, etc. This challenge was deeply threatening, psychologically and socially. For these religious leaders, to abandon their beliefs would have meant an entire upheaval to how they had always lived their lives and the social organization that had always guided it.

There is, however, more to this story. The New Testament tells of many followers of Jesus, some of whom were from those same circles of religious leaders who rejected Jesus. So, how did they develop ears to hear and eyes to see? This very important question with implications for you and your life—how can you develop ears to hear and eyes to see? Although I will take up this question from the perspective of psychological research in the next part of this blog, I’d like to hear your thoughts: what do you think is important in the process of changing beliefs? How do you think the process of motivated reasoning or shared reality inhibit belief change?

What are your thoughts? Share below-CBU student comments left within a week of the publication of this blog will be entered into a raffle for a CSHB external battery to keep your phone charged when you are on the go. Winners notified via email.

Erin I. Smith, Ph.D., is an associate professor of psychology and the director of research for the Center for the Study of Human Behavior(CSHB). Her Ph.D. (University of California Riverside) is in Developmental Psychology, where she studied the development of religious and scientific cognition. Her current research interests focus on the psychological and cultural influences on the science/religion dialogue and the distinct role of church in children’s development, especially for children who have experienced adverse life experiences.