Mikaela Schmierer

STEP 1: “Now finish the work, so that your eager willingness to do it may be matched by your completion of it, according to your means.” (2 Corinthians 8:11)

A finished manuscript or rough draft must be completed to begin the editing process. This will help to cut out unnecessary and excessive editing during the writing process to detract from the overall story. Although you may want to edit or completely rewrite a scene, hold off on that feeling and finish the scene or chapter as close to your intended plot arc as possible. If the need to edit or rewrite persists, I recommend using a second document as a placeholder and comparing the two written versions. A fully-fledged manuscript before beginning editing will also help maintain consistency in voice, style, diction, and a thorough plot.

STEP 2: “Proofreading… is a basic and mechanical process.”

The editing process should feel rudimentary, simple even as you begin to sort through your work. To start editing, read through the manuscript entirely, either printed or online, based on which is better for you. When you read through, you want to have a couple of things at your disposal and ready for the read-through, such as a highlighter, a pencil or underlining tool, and something to take notes on, like sticky notes. You should focus on three main things as you read through your rough draft. Grammar and punctuation will be principal elements you look for and will notice immediately. Voice and style, however, might be tricky to keep tabs on. To help keep your story clear and concise as you edit and revise, I suggest keeping a system with notes and ideas either online or on an easily discernible notepad– you do not want to lose this! Another aspect you want to keep an eye out for is tense and perspective. If you switch between them in the work, you want to ensure it is continuous and consistent– such as flashbacks or prologues. Otherwise, pick the tense that makes the most sense for your writing style and the story itself.

STEP 3: “Perfect is the enemy of good.” –Voltaire

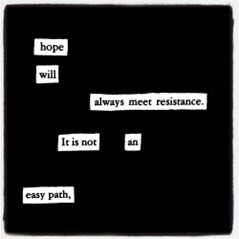

After considering the essential editing elements, your first draft’s new layout and document will be pretty messy. But do not fear! The first draft, the second draft, and even the fifth draft will not be perfect. A good reminder in the earlier stages of self-editing is to have grace with yourself and to trust the process. The proverb “consistency is key” is a highly regarded phrase for a reason. Messiness isn’t always bad; it can lead to patterns and ideas being more exposed from your work than you initially noticed.

STEP 4: “A schedule defends from chaos and whim.” –Annie Dillard

Getting to your first draft and setting aside time to edit can seem daunting, but let’s reshape the approach to the revision process as just that. Processes are meant to take time, and if they’re finished during the first attempt, you risk overlooking details that can be vital to the work. Having a schedule or game plan, as basic or detailed as you like, can be a great tool. One way to approach a schedule can look like setting aside thirty minutes a day to crack open your manuscript, reading through a couple of pages at a time, and making some marks or notes. Another way could be going through a chapter or section per day. At least having a schedule will help relieve some stress and anxiety surrounding wrestling with the editing process, offering options such as revising characters and settings to redoing entire scenes. This is all according to your timetable and how much time you want to set aside. That way, you have control over the entirety of your work.

STEP 5: “Comparison is the thief of joy.” – Theodore Roosevelt

Once self-editing has begun, it is important to remember that your work is yours, the writing will be distinctly individual, and other’s works will vary in audience and recognition because their works are starkly theirs. Try your best to maintain confidence in yourself and your ability to write. While going through the editing process, keep your mind set on the story you want to tell and not how it compares to other works. Worry and nitpicking won’t help in the end regarding the final product, so keep your head high and aim for the stars.

Works Cited

The Bible. YouVersion. NIV, 1 Corinthians. https://www.bible.com/

Dreyer, Benjamin. Dreyer’s English : An Utterly Correct Guide to Clarity and Style. Random House Publishing Group, 2019, pp. 9.

Dillard, Annie. The Writing Life. HarperCollins Publishers, 2009, pp. 32.