Come read the newest edition of CBU’s literary journal and enter into the true spirit of Christmas.

Here’s a sneak peak:

Come read the newest edition of CBU’s literary journal and enter into the true spirit of Christmas.

Here’s a sneak peak:

Writing poetry is challenging. It’s as simple as that. The very act of setting the right words in the right order in just the right way is sometimes such an insurmountable endeavor that most simply do not attempt it, and the hard-headed ones keep at it. The number of issues, pitfalls, and conundrums writers face are innumerable. However, among the challenges that I’ve seen with many poets at the beginning of their craft both as a tutor of four years and as an editor of this Spring’s edition of The Dazed Starling, one challenge stands out as both glaring and easily fixable: they don’t know what contemporary poetry really looks like or what its tenets are, and as a result, they write in styles that are outdated and destined to flop.

However, as much as this issue has to do with a lack of familiarity, I don’t blame any young poet doing their best to attempt a Wordsworthian lyrical ballad or a Shakespearian sonnet, no more than I blame myself for attempting something so cringeworthy. I blame the fact that the first time I read a lick of contemporary poetry that made sense, (that wasn’t so blatantly avant-garde or simply some photo on Instagram), wasn’t until I took a creative writing class in my second year of my undergraduate study. I blame the fact that as a supposed major in English Literature, the only frames of reference I had to write a poem were Wordsworth, Shakespeare, Tennyson, and Dylan Thomas. All beautiful poets in their own rights and in their own times, but not our time, not in 2022.

As much as I’ve written in first person, this issue isn’t unique to me. It is so ubiquitous, in fact, that much of the poetry I’ve read (and much of the poetry I wrote) falls back on some archaism, no matter how contemporary it attempts to be, and some read completely as if they’ve never seen any poetry written after 1850. This is likely because, if my experience serves me right, they simply haven’t read enough, as I certainly did not. Names like Dana Gioia or Mary Oliver rang no bells, felt obscure, and their poetry even more bewildering.

“Are these even poems?” I asked.

Certainly, they are. They just follow different conventions than what we, as readers and aspiring poets, are used to.

Despite the fact that this post is a rant about not hearing Gioia’s “Prayer” early enough, I am no expert in the “tenets” of contemporary poetry. For one, there are no “tenets” per se; there are only trends, broad tendencies, commonalities in poems written today that we can just barely put our fingers on. If any neophyte poet wishes to grasp these trends, I would recommend Mary Oliver’s A Poetry Handbook as a starting point. I return to this book often as a source of inspiration and correction for my own poetry, and as such is indispensable.

Short of buying a book, however, I do want to recommend one idea to every poet that might read this that is having trouble updating their style, besides actually reading contemporary poets, two of which I have already mentioned: Write as simply and plainly as possible. Aspiring poets, myself included, are often guilty of taking off our “normal speaking” hats, and putting on our “Poetry hats,” (there is usually a quill that sticks out of the brim, very stylish), and we write in ways that to any other reader sounds like we are doing our best impression of our favorite romantic poet. Take the hat off, and throw it across the room, even hide it in your attic if you have one, because as long as you try to sound like someone else, particularly if they have been dead for over two hundred years, you will never write like yourself, or anyone else alive for that matter. I will take a cue from Mary Oliver’s book, and ask that you write as if you were speaking intimately to your reader: with intent and intensity, but not overblown, or with false poetic

The difference between fiction and reality? Fiction has to make sense.

Tom Clancy

When people typically read a story, they tend to connect with the characters or the story’s world. These connections are not simply enjoying the world or having a favorite character but connecting the fantasy to the readers’ reality. So now, the character the readers love may stem from their background and their relationships with the real world and its people. Although many readers and scholars would agree that associating their real-life experiences with the story brings the imagination to life, Felix Martinex-Bonati disagrees. In his article, “The Act of Writing Fiction,” he explains why attaching one’s life to the story destroys the narrative and the imagination.

It may sound unbelievable that attaching yourself to the story can hinder the piece because part of human nature is that we form bonds. These bonds aren’t just with people and animals, but they can be with anything capable of interaction, such as T.V. shows, movies, nonfiction, and fiction stories and music. The way a character is designed or interacts can trigger a memory, potentially giving readers more enjoyment and another reason to keep reading. The readers may also see themselves within a character or world making it more immersive or providing an escape from reality. With these bonds being connected, it raises the question of is it good, is it better to have this immersive world, or should it stay a fantasy and be pure fiction.

One of the problems Martinex-Bonati addresses is when people associate their life with the story, they “succeed only in reading, unsatisfactorily, some fragments of it, and we find ourselves forced to give up this task” (1). Linking with the story takes away its credibility. It makes the fictional world crumble because expectations must be met since that is how the reader imagined the story or character would act. If the fictional world created can be controlled by reality and the reader’s perspective, is it still considered a fantasy world if the reader is in it? The line between reality and fantasy gets blurred, and if the two struggle to be distinguishable, the illusion is gone.

As writers and readers, we must ask ourselves which is the better option. If you plan on writing, would you want the world to be immersive and have the audience feel connected to it? This outcome could lead to a polarizing response since some may love the story’s direction while others may hate it and try to change its direction somehow because it’s not how they would have acted or how they imagined something should have been. The other option is asking yourself is better to have the line separated, making the fiction unattached with a potential loss of readers due to the lack of immersion, which may lead to fewer backseat writers? Both options have positives and negatives, so it is up to you to decide if there should be a barrier between reality and fantasy.

Martínez-Bonati, Félix. “The Act of Writing Fiction.” New Literary History 11 (1980): 425.

I am not a creative writer.

I have never been, and I probably never will be. The problem for me is the creative aspect. Give me any topic or essay assignment, and I can write my heart out. But, when you ask me to make up my own story, poem, or topic, that is when I completely blank. It was not until about eight weeks ago that I started to have to do some creative writing. In my final semester of college, I had to take one last English class to graduate, and it turns out that class was “Introduction to Creative Writing.” These past few weeks in the class have been a struggle for me. It has been hard to develop my own ideas and translate them onto paper. While I have been having a rough time with this, I have turned more towards my textbook to give me some ideas about what I should write. So, if you are like me and struggle to come up with ideas for that next short story or poem, look no further because I have a few topic ideas for you.

Topic 1: Write about a routine.

For the first poem that I had to complete, I wrote about my night time routine. When writing about my night time routine, I described that exhausting feeling about coming home from work and then going into my relaxing night time regime. What’s great about this topic idea is that everyone has some sort of routine. Whether it is a morning routine, a typical drive that you have to take, a workout regime, or making memorized meals, many of the tasks in our daily lives consist of some sort of routine. These routines can elicit many different emotions, which further expands the topic. By writing about a routine, you write about what you know and describe the emotions and actions that go into completing that task.

Topic 2: Write about an object.

One popular activity to do these days is to go out shopping and more specifically, thrift shopping. So, while going out and doing this activity, find an intriguing object or clothing piece and center a story around it. Have the character be attached to that piece, whether they wear it or have it in their home. Antique pieces found thrift shopping have a life before being sold to the store. By coming up with ideas on where the piece has been, you can start creating many story concepts.

Topic 3: Write about an image.

While in my creative writing class, our professor put up a few images onto the screen and told us to write about them. We were able to write about either what was seen in the image or to make up a story with that image in mind. This idea offered a lot of possibilities, but by having an image in mind, it does not seem like you are starting from scratch. You have an idea and can build upon it. Along with this idea, writing about a painting could also spark an idea. Write about the Mona Lisa or The Starry Night. These pictures and images will initiate a great start to a story.

For those unsure of what prose might be, the simple answer is anything that isn’t poetry. So instead of following a strict structure such as rhyme or meter, the only structural requirement is that it follows conventional grammar. By this definition – I’m sure everyone has written in this style, and while prose can be anything from academic to casual, I want to focus on creative prose. If you find that you are more of a poetic writer, this probably won’t be helpful. Although you are more than welcome to stay.

Now let me get to the point of this post. Every writer I have met falls into one of three categories in writing and planning their stories. The plotter outlines every idea and situation, the pantser just comes up with an idea and figures out the rest as they write (“by the seat of their pants”), and finally, the plantser, who typically does equal parts of both planning and winging it. None of these are right or wrong when it comes to writing. It just depends on what works for you. Personally, I am the planster. The plotters will like the first book on the list best. However, it is helpful for everyone and is a good idea to read, whether you utilize the ideas or not.

1. Outlining your Novel by K.M. Weiland

This book is a fantastic place to start because it highlights the different types of outlines and teaches the reader how to make and use one effectively. Who knows, maybe you are a plotter after all. The second book on this list is by the same author but doesn’t lean towards any specific group. Instead, it focuses on creating characters.

2. Creating Character Arcs by K.M. Weiland

Whether we like it or not, characters are what make or break a story. It doesn’t matter if the plot is amazing if the reader doesn’t like or care about the characters. This is why I am recommending this book. The more you know about the character and their arc, the more realistic they become. Not to mention easier to write. Finally, the third book on the list is what the pantsers will love. The book I put on here is one I am still going through myself but can be easily supplemented with another one of a similar style.

3. 400 Writing Prompts

Sadly, I could not find the author of this. But I placed a prompt book on the list to encourage writing even the most ridiculous ideas. Sometimes the best way to learn is to do. Remember, all writing advice is simply advice. In the end, you figure out what works the best for you. But these books can certainly help the process.

Margaret Atwood once wrote “You’re never going to kill storytelling, because it’s built into the human plan. We come with it.” She was not talking about one group of people over another, not talking about a single career, she was speaking universally. Every human in existence has come with the innate ability to tell a story. Whether it be their own story, a story about somebody else, or even a story in a fantastical world, it doesn’t matter; the ability is instinct.

There are people who claim that creative writing and professional storytelling should be kept to those who pursue it as a career–I claim the opposite. I base this claim on Margaret Atwood’s words and my own experiences. Storytelling does not always have to come from a view of professional careerism; it can come from a place of love and passion for the craft. It can be an escape from reality for those whose lives seem to offer less than magnificent circumstances. A work written from passion can be just as amazing as one from somebody who spends their life dedicated to authorship. Claiming that writing belongs to one group is like asserting that breathing is withheld from those who have fully functioning lungs–it’s ridiculous. Storytelling is as natural to humans as breathing and as such it should be recognized as being just as important and universal.

In every sense of the world, storytelling is around us, maybe not in a written medium but perhaps in an expansive colorful design. There is no one way to tell a story, so why would we claim it belongs to only a single career (or major!), style, or genre. I want to read stories about dragons and magic just as much as I want to read an inspiring memoir about the hardships of living in different circumstances. Billions of people, trillions of stories, and all of them are part of our universal human need to tell, and to receive, stories.

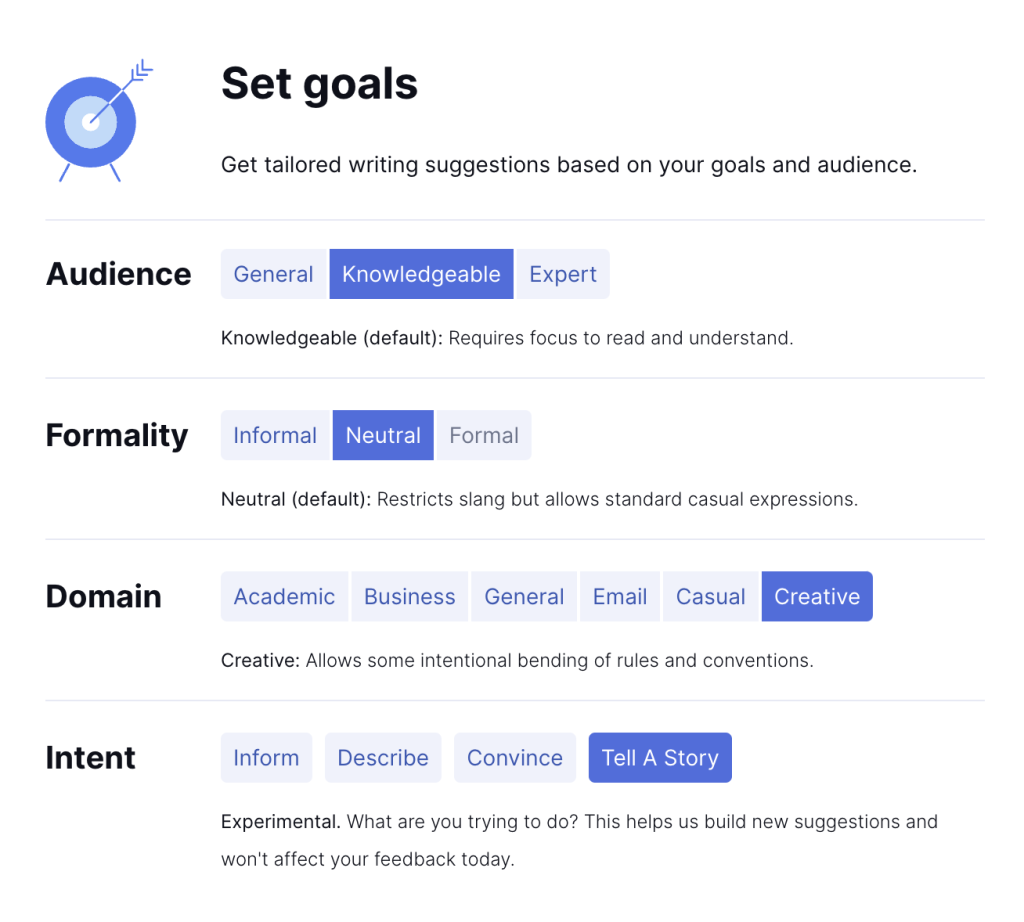

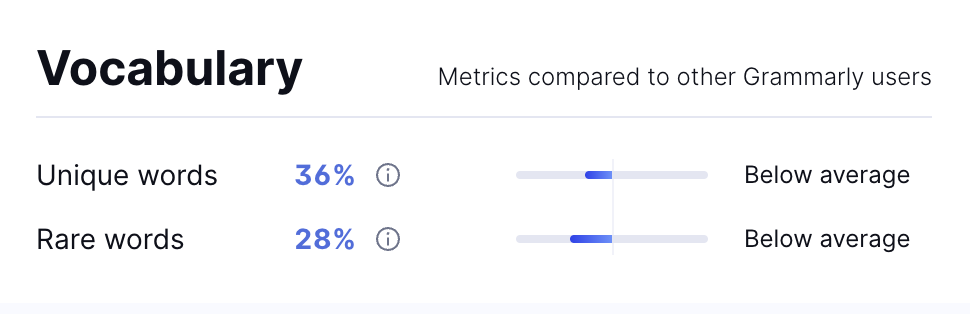

Yes, you read that right! Grammarly is for more than writing emails and essays—even creative writers can benefit from grammar assistance from time to time. And, lucky you, current CBU students can sign up for a personal Grammarly Premium account for free through the University Writing Center! Contrary to popular belief, Grammarly is so much more than fancy spellcheck—it is an AI-powered application that highlights writing mistakes and suggests corrections, acting as a personal editor to help you on your way to publication. Even the most experienced writers can benefit from Grammarly’s eye on their work—we often know what we are trying to say so well that we skip over minor mistakes that would trip up a reader. Additionally, with a Premium account, you can use Grammarly to define writing goals that will provide tailored suggestions in categories of audience, formality, domain, and intent. There is even a built-in creative writing option that allows for the intentional blending of grammar rules and conventions! With these available settings, you can use Grammarly for any writing situation, from a short email to a doctoral thesis.

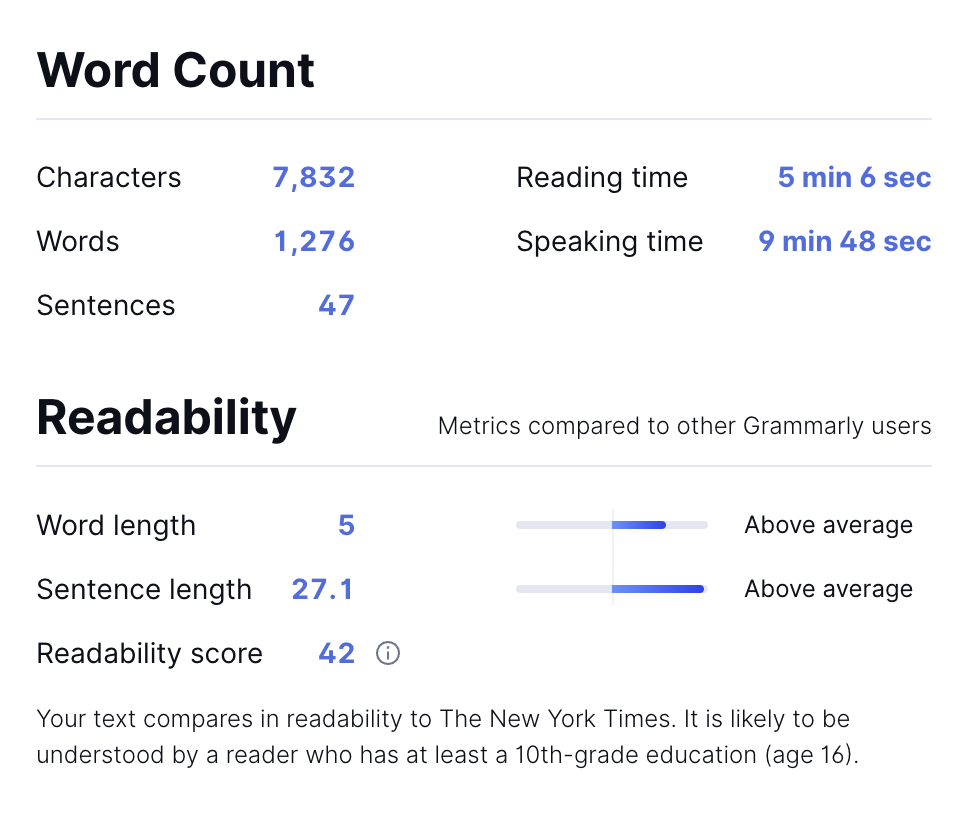

To help you, Grammarly also provides a score based on correctness, clarity, engagement, and delivery, giving suggestions on how you can improve these aspects of your writing. However, it is important to note that Grammarly is still not perfect, though it improves each time it is used. Some suggestions it offers may completely change what you had been trying to say in a sentence, so make sure to think critically about its changes as you review them. For creative writing especially, it is important to use these suggestions to your discretion to retain your authorial voice! Less noticed, but still cool, Grammarly keeps a record of statistics such as word count, readability, and vocabulary, as shown below. In creative projects, such as writing a children’s book or short story, the readability rating can be incredibly helpful in making sure your audience understands your writing.

If you have yet to sign up for your free, CBU-affiliated, Premium Grammarly account, do it now! It takes less than five minutes, and the Writing Center has put together an informative tutorial video on signing up and using Grammarly to its full potential. The sign-up link and the video can be found at the link below. Happy writing!

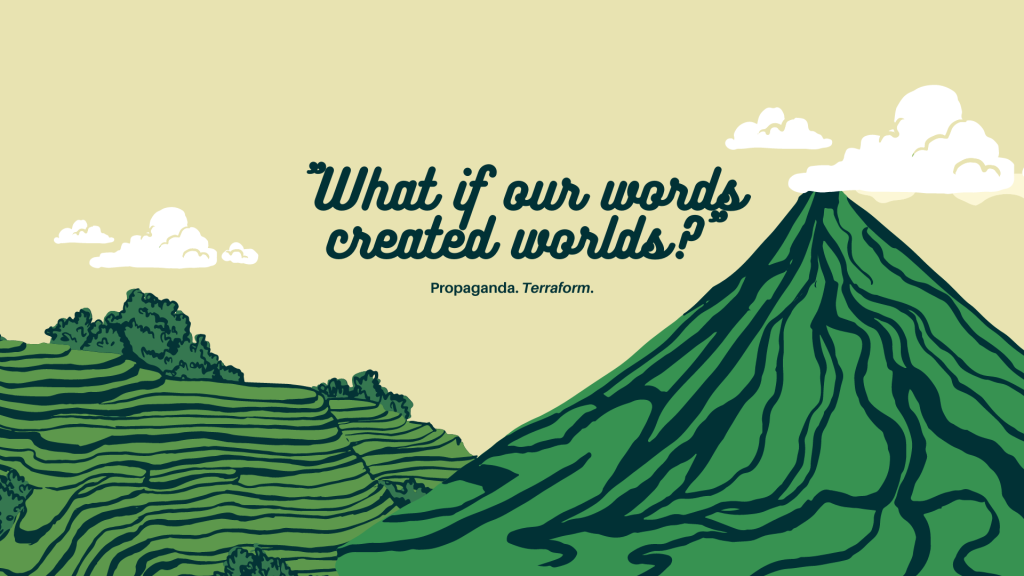

In his book, Terraform, published in 2021, Chrisitan rapper, spoken word artist, and poet Jason Petty–who goes by stage name Propaganda– writes of bettering our world through terraforming. Yet, what exactly does terraforming mean? “In science fiction,” Propaganda writes, “when someone discovers a distant planet that could possibly sustain life yet is still too hostile an environment for humans in its current state, a team of scientists and engineers must work over decades, or maybe centuries, to make the air breathable, the ground fertile, and the climate more suitable for human flourishing. They must get that rock to do what Earth does naturally. This process is called terraforming” (5). However, Prop’s message is not referring entirely to the scientific application; instead, he is pointing to the power of stories and perspective.

Born in the difficult regions of Los Angeles, California, Propaganda shares parts of his life growing up, touring, and connecting with God by familiarizing himself with others. It is through the foundation of words and thoughts that Prop realizes one can grow and live intentionally. “What if our words created worlds?” Words, Prop states, are what built nations, preserved identities, and nurtured healing through the trauma of the past and present. In words, we find pieces of ourselves and pieces of the earth. Take, for example, the book of Genesis. The book tells the planet’s origins and our relationship with God. Before the book was written, it was told through the spoken word. In Genesis, God created light, sky, water and land, and pretty much the whole universe. This ingenious self-sustaining creation brings questions about its miraculous functions: How can the universe be expanding yet never-ending? What tells the cell to split? If God’s creation is sacred, then is the soil that our ancestors have lived on and been buried underneath sacred too? The answer is yes, but how often do we find ourselves distracted by our own creation? Where do we see our purpose? “We are all we got,” Prop reminds readers amidst the distractions of our culturally polluted world (83). Media, money, defamation, and cultural division hinder us from connecting with God, the planet, each other, and ourselves.

Rich with creative poetry and thought-provoking challenges for readers to participate in, Propaganda explores what it means to restore our well-being and planet. To terraform our planet, to keep it from becoming uninhabitable like Mars, we must first learn to grow ourselves and help others along the way. Be the future you want to see. Acknowledge the cultural toxicity around you, whether it be in thoughts or actions, learn to overcome it. We are, after all, all that we have got.

Works Cited

Propaganda. Terraform. HarperCollins, 2021.

I’m fairly certain that, throughout the long history of scribblers, the vast majority of wannabe writers have, at some point, dropped their quills/pens/keyboards, put their head between their hands, and stared at the wall in that unique stare that signifies Existential Crisis to anyone unlucky enough to be in the area. Why am I doing this? Mom was right. I should’ve gone to medical school and become a proctologist. Most writers will, after all, acknowledge that writing doesn’t pay the bills. Aside from a select lucky handful, born in privileged positions at judicious points in history, most writers really don’t get the fame, fortune, and fan clubs that are practically handed to those at the top of the Times’ bestseller lists. Nor does writing pull carbon from the atmosphere or recede the floodwaters or house the homeless or take guns off the streets or do anything, really, to resolve any number of panic-inducing Hot Button Issues bandied about on the 24-hour news cycle (some socially-inclined writers might get persnickety and argue, here, that they’re raising awareness of said Hot Button Issue, but, let’s be honest, they’re probably preaching to the choir. Nobody’s going to pay twenty dollars for a novel written on a topic that excites them to apoplectic rage).

Hence the title of this blog post. Cui Bono is Latin (pretentious, I know) for “Who stands to gain?” Who benefits? What’s the motive? The classic question of hard-boiled detective novels. But really, who does benefit from writing? Some might argue that the chance, albeit slim, at immortality and wealth is worth it, which, I suppose, would put career writing in that same category of practical retirement investments as playing the lottery. Others might take a more utilitarian path, claiming that writing about pressing social issues justifies the difficult writer’s life. That’s a noble goal, and I’m not going to denigrate that kind of self-sacrifice. Certainly, great works of writing have, on occasion, changed the world for the better. But really, there are other, more practical ways of enacting change. And furthermore, a great many of the canon literary works – and many of the books found in literary traditions outside of the Western canon, for that matter – don’t have pressing social commentary at their hearts. So, Cui Bono?

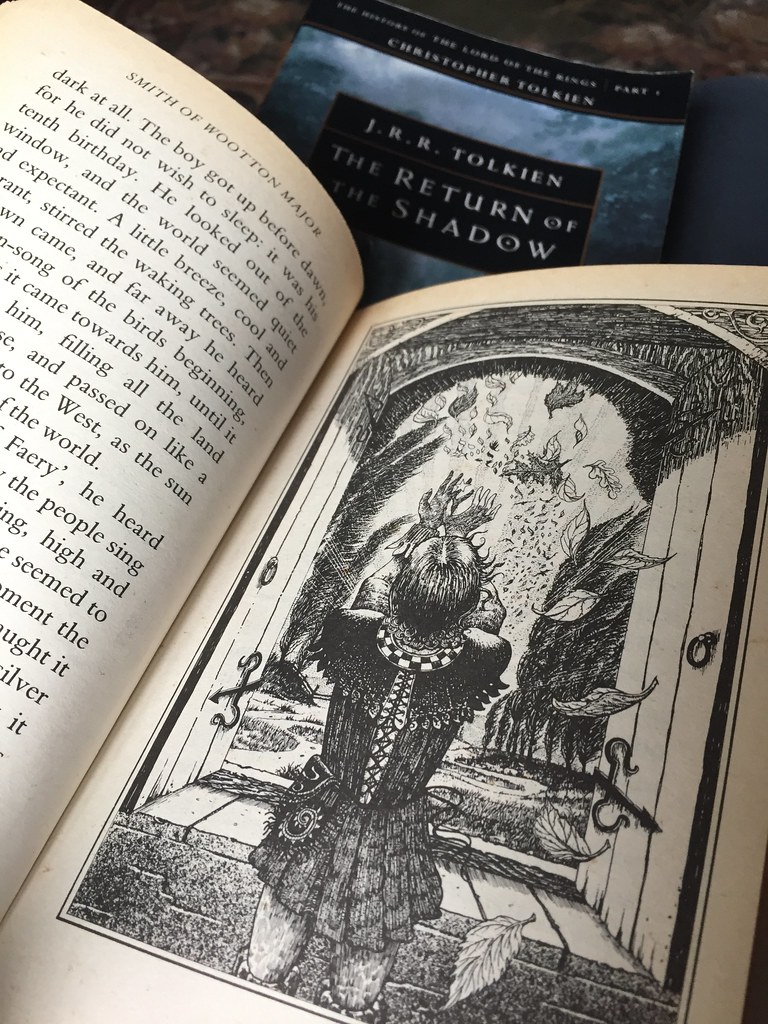

To explain (my) answer to that question (there are, of course, a great many more answers to that question), I’d like to look at a lesser-known story of J.R.R. Tolkien’s, Smith of Wootton Major. Now, as I’ve been brought up first in Christian homeschool networks, then in two separate private Christian universities, I’ve been exposed to an educational environment that grants Tolkien a status somewhere between minor literary sainthood and demi-deity. Despite this, a great deal of the man’s devoted fan club hasn’t read anything beyond his Middle-Earth legendarium, which I think is a great shame. Smith of Wootton Major is the story of a young man named Smith, who, by plot contrivance, swallows a fairy-star. As a boy, Smith’s village has a ritual wherein the head cook of the village creates a Great Cake, an artistic magnum opus that contains many trinkets for the village children to find when they eat the Cake. One of these trinkets is, of course, the star, which Smith accidentally eats. The star allows him to travel throughout fairy-land, having a great many wondrous and terrifying adventures, until he, inevitably, grows old and must pass the star on to the next generation of children.

This, I think, is an appropriate metaphor for the benefits of artistic endeavors. An artistic creation – the Cake – contains something transcendent, something magical, something greater than itself. It is given to another, and in so doing, allows him to see beyond the physical world, to transcend into a more beautiful world. Smith cannot keep this gift within himself, so he must give it to another. Great literature can, and should, reach for a transcendent reality; it should attempt to place the author and the reader within the cosmic drama of the human story. I think this principle can apply to all art, really, but since this is a writing blog, I’m going to limit my scope of analysis to literature. It should seek to make physical reality greater than it seems to the senses; the sun brighter, the wind crisper, flowers sweeter-smelling, etc., etc. In other words, it should make life more desirable.

At this point, I’ve probably lost quite a number of you. This kind of take seems naïve and cheesy, particularly in light of the awareness of the never-ending torrent of all-too-human evil that defines the modern era. Our ancestors could believe in fairy tales, but they had the luxury of not living in a world with nuclear bombs and climate change and cronyist corporate overlords. To which I say, first, blanket cynicism is as defensible and intellectual of a position as blanket naïveté. Second…yes. You’re right. Good writing can’t exist in happy-go-lucky-land, playing with rainbows and ponies and whatnot; that’s the domain of children’s television and the source of a never-ending stream of gratingly catchy singalongs. In fact, I don’t think good writing ever did exist in that state. It’s practically a meme at this point how gruesome and brutal some of the old stories, even fairy tales, were. In my chosen example, Tolkien’s Smith’s world is as violent and dangerous as it is beautiful. Smith is often frightened by what he sees, and the real world is no different. A writer that doesn’t reflect the reality of the world, with all that is terrible about it, is going to ring hollow to a discerning, informed reader. But for all this, writing that can reach beyond the corruption, terror, discrimination, and waste of the world is just…that much more powerful. Writing is, really, more of a journey of authorial self-deception than a gift given by the author to the reader, whereby the author must convince themselves that there is something desirable about life and invite others along for the journey. Good writing, desirable writing, writing that benefits both self and others, acknowledges and embraces the surrounding horror and notes that, in spite of everything around it, there’s something that makes life worth living.

During both my writing classes and casual conversations with friends, writing is often agreed upon as intimidating. We often feel as if writing is like holding a microphone in hand while everything we say through that speaker is magnified with a stupid stance. With a mindset like that, we have no resolution for the fear but consistently return to the origin of that fear. Two factors trigger this fear: either we have an empty head, no inspirations, no enthusiastic feelings to input, or we uphold too much self-esteem that constrains us from thoroughly expressing our sentiment. I would like to offer a writing mechanism for you to practice using on such fears until, eventually, you’re confident in honing your writing skills. I call it “manufacturing your own Wunderkammer.”

“Wunderkammer” is a German word that translates as the cabinet of curiosities. By definition, Wunderkammer stores and exhibits offer a wide variety of objects and artifacts, with a particular leaning towards the rare, eclectic, and esoteric. The philosophy is that “through the selection of objects, they told a particular story about the world and its history.” So, what does it mean to manufacture our own Wunderkammer?

In general, we should first immerse ourselves in a variety of reading, accumulate ideas, and make connections with great thinkers across time. Then, having a notebook of inspiring quotes and ideas, and reflecting on them will help construct a Wunderkammer in our mind, like the mind palace in BBC’s Sherlock Holmes. Those precious things we treasure up will surely lead to a burst of imaginative fountains in our empty vase that we can then pour out to others.

Reading until this point, some of you might question the originality of our writing if we are constantly absorbing the nutrition from the previous literary giants. And, to some extent, Wunderkammer will remain a romanticized expression if we skip the last and most significant step– we need to invite people into this wonderful and generous house of information, in which we share and potentially even become source of imaginative knowledge.

Writing will still and always be intimidating, but just like Hemingway states, “There’s nothing to writing, all you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.” The lucky thing is, we get to choose whom we are sharing our writing with, and who obtains the privilege of entering our Wunderkammer.