Cui Bono?

Benjamin Lang

I’m fairly certain that, throughout the long history of scribblers, the vast majority of wannabe writers have, at some point, dropped their quills/pens/keyboards, put their head between their hands, and stared at the wall in that unique stare that signifies Existential Crisis to anyone unlucky enough to be in the area. Why am I doing this? Mom was right. I should’ve gone to medical school and become a proctologist. Most writers will, after all, acknowledge that writing doesn’t pay the bills. Aside from a select lucky handful, born in privileged positions at judicious points in history, most writers really don’t get the fame, fortune, and fan clubs that are practically handed to those at the top of the Times’ bestseller lists. Nor does writing pull carbon from the atmosphere or recede the floodwaters or house the homeless or take guns off the streets or do anything, really, to resolve any number of panic-inducing Hot Button Issues bandied about on the 24-hour news cycle (some socially-inclined writers might get persnickety and argue, here, that they’re raising awareness of said Hot Button Issue, but, let’s be honest, they’re probably preaching to the choir. Nobody’s going to pay twenty dollars for a novel written on a topic that excites them to apoplectic rage).

Hence the title of this blog post. Cui Bono is Latin (pretentious, I know) for “Who stands to gain?” Who benefits? What’s the motive? The classic question of hard-boiled detective novels. But really, who does benefit from writing? Some might argue that the chance, albeit slim, at immortality and wealth is worth it, which, I suppose, would put career writing in that same category of practical retirement investments as playing the lottery. Others might take a more utilitarian path, claiming that writing about pressing social issues justifies the difficult writer’s life. That’s a noble goal, and I’m not going to denigrate that kind of self-sacrifice. Certainly, great works of writing have, on occasion, changed the world for the better. But really, there are other, more practical ways of enacting change. And furthermore, a great many of the canon literary works – and many of the books found in literary traditions outside of the Western canon, for that matter – don’t have pressing social commentary at their hearts. So, Cui Bono?

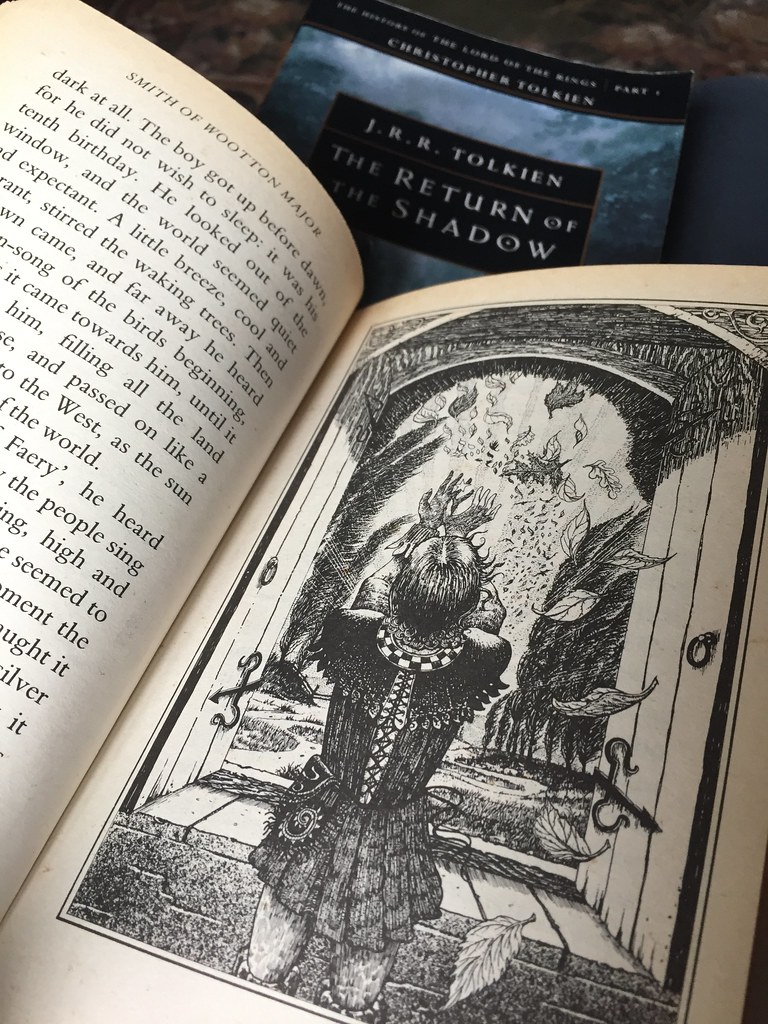

To explain (my) answer to that question (there are, of course, a great many more answers to that question), I’d like to look at a lesser-known story of J.R.R. Tolkien’s, Smith of Wootton Major. Now, as I’ve been brought up first in Christian homeschool networks, then in two separate private Christian universities, I’ve been exposed to an educational environment that grants Tolkien a status somewhere between minor literary sainthood and demi-deity. Despite this, a great deal of the man’s devoted fan club hasn’t read anything beyond his Middle-Earth legendarium, which I think is a great shame. Smith of Wootton Major is the story of a young man named Smith, who, by plot contrivance, swallows a fairy-star. As a boy, Smith’s village has a ritual wherein the head cook of the village creates a Great Cake, an artistic magnum opus that contains many trinkets for the village children to find when they eat the Cake. One of these trinkets is, of course, the star, which Smith accidentally eats. The star allows him to travel throughout fairy-land, having a great many wondrous and terrifying adventures, until he, inevitably, grows old and must pass the star on to the next generation of children.

This, I think, is an appropriate metaphor for the benefits of artistic endeavors. An artistic creation – the Cake – contains something transcendent, something magical, something greater than itself. It is given to another, and in so doing, allows him to see beyond the physical world, to transcend into a more beautiful world. Smith cannot keep this gift within himself, so he must give it to another. Great literature can, and should, reach for a transcendent reality; it should attempt to place the author and the reader within the cosmic drama of the human story. I think this principle can apply to all art, really, but since this is a writing blog, I’m going to limit my scope of analysis to literature. It should seek to make physical reality greater than it seems to the senses; the sun brighter, the wind crisper, flowers sweeter-smelling, etc., etc. In other words, it should make life more desirable.

At this point, I’ve probably lost quite a number of you. This kind of take seems naïve and cheesy, particularly in light of the awareness of the never-ending torrent of all-too-human evil that defines the modern era. Our ancestors could believe in fairy tales, but they had the luxury of not living in a world with nuclear bombs and climate change and cronyist corporate overlords. To which I say, first, blanket cynicism is as defensible and intellectual of a position as blanket naïveté. Second…yes. You’re right. Good writing can’t exist in happy-go-lucky-land, playing with rainbows and ponies and whatnot; that’s the domain of children’s television and the source of a never-ending stream of gratingly catchy singalongs. In fact, I don’t think good writing ever did exist in that state. It’s practically a meme at this point how gruesome and brutal some of the old stories, even fairy tales, were. In my chosen example, Tolkien’s Smith’s world is as violent and dangerous as it is beautiful. Smith is often frightened by what he sees, and the real world is no different. A writer that doesn’t reflect the reality of the world, with all that is terrible about it, is going to ring hollow to a discerning, informed reader. But for all this, writing that can reach beyond the corruption, terror, discrimination, and waste of the world is just…that much more powerful. Writing is, really, more of a journey of authorial self-deception than a gift given by the author to the reader, whereby the author must convince themselves that there is something desirable about life and invite others along for the journey. Good writing, desirable writing, writing that benefits both self and others, acknowledges and embraces the surrounding horror and notes that, in spite of everything around it, there’s something that makes life worth living.

0 Comments