by Ken Nehrbass

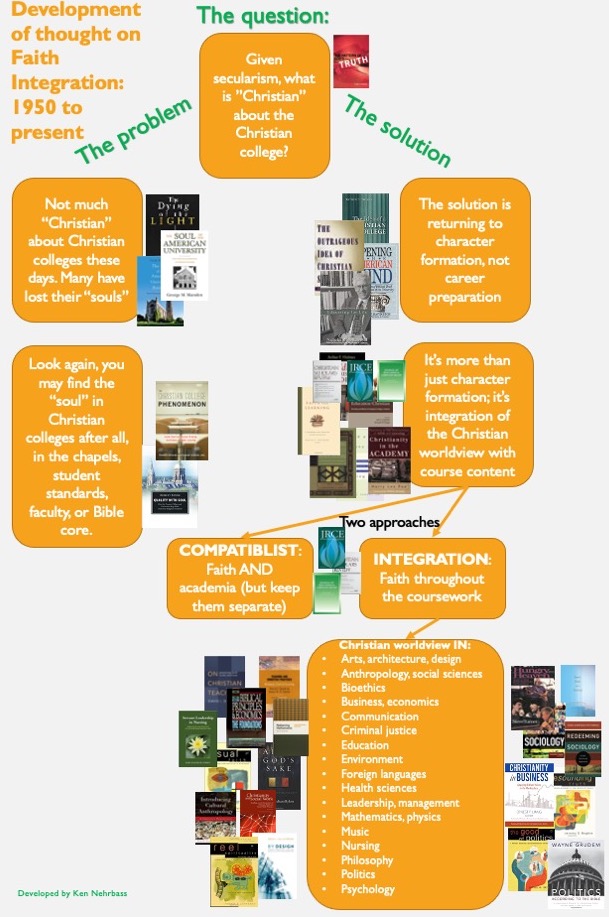

This short blog post describes the development of thought in “faith integration” literature.

Harvard and Yale used to be trustworthy training grounds for pastors- what happened? Why does it seem so many colleges with a Christian heritage have drifted toward secularism? This concern for mission-drift was evident even by the 1950’s. Gaebelein’s (1954) Pattern of God’s Truth worried that Christian colleges supplied Christianity merely as a “chocolate covering” (17). Faith was either tagged on, or kept separate, from academia. Gaebelein suggested that instead we should work out an integrated “world and life view” (18) because “all truth is God’s truth” (21).

But does the Bible really teach us about subjects that students need to take in college, such as physics and biology? Gaebelein argued that while the Bible doesn’t answer all questions, all questions are worth pursuing; and all knowledge (or truth) can be traced back to the Author of creation, who is Truth. This assertion that truth- wherever it may be found- is connected to God has been referred to as the “two books” epistemology (nature and scripture), which was first articulated by church father Origen, and later described by Francis Bacon in his 1607 book The advancement of learning. It was also described in the Belgic Confession of 1561.

We know [God] by two means: first, by the creation, preservation and government of the universe; … Secondly, he makes himself more clearly and fully known to us by his holy and divine Word, that is to say, as far as is necessary for us to know in this life, to his glory and our salvation

The Belgic Confession of 1561

Have Christian colleges really lost their soul?

A number of landmark works on faith integration traced the decline of the Christian university into secularlism. Marsden (1994) and Burtchaell (1998) argued that Enlightenment, rationalism, secularism, postmodernism all contributed to the loss of the “soul” in historic Protestant universities.

But more recent works have challenged this narrative, finding evidence of “soul” – depending on how you define it. Joeckel and Chesnes (2011) carried out extensive qualitative research on the state of CCCU schools; finding there is not as much ”Marsden Effect” as predicted. And Benne’s (2001) “Quality with Soul” find faith integration at six major Christian-heritage schools, in the chapels, hiring practices, community life standards and Bible requirements. But are they making the connections between Christianity and their academic disciplines?

Are Christian colleges anti-intellectual?

A major concern that faith integrationists had to deal with was the accusation that fundamentalist Christian colleges were anti-intellectual. In other words, they were heavy on faith, but light on academia. Consider, for example, Noll’s (1994) Scandal of the Evangelical Mind which argued that evangelicals have been anti-intellectual, and need to move away from creationism. My review of the book Fundamentalist University traces the responses that Christian colleges have had to the modernist-fundamentalist divide.

In fact, Christian scholars have taken various approaches toward secular academia, as mapped by various faith integration scholars. Akers, G. H. (1977) believed FI happened along one of four approaches: disjunction, injunction, conjunction and fusion. Hasker’s (1992) taxonomy was: compatiblist (no tension), reconstructionist, transformationis. Badley (1994) noted five approaches: fusion, incorporation, correlation, and perspectival integration (the last is common in CCCU). Langer’s (2012) innovative taxonomy uses the metaphors of the butcher, baker and candlestick maker.

Authors on faith integration have arrived at two solutions for getting the “soul” back into the college campus (note these solutions are not in contradiction with each other; they are different approaches to faith integration). The first solution is to focus on character more than careers. And the second is more ambitious: To integrate the Christian worldview throughout the subjects we teach.

Solution #1: It’s about character, not career

One answer to the question “What is Christian about Christian colleges” was that we exist for formation of character and thought, not just for career preparation. Arthur Holmes’ (1975) Idea of a Christian college builds a case for the liberal arts– to “cultivate the creative and active integration of faith and culture”(6). Wolterstorff (2002): Christian education leads to a way of living, not just thinking; argued that the Christian worldview will holistically, rather than piecemeal, provide perspectives on the arts, literature, capitalism.

Solution #2: Develop a Christian worldview throughout the academy

Much recent work on FI has explored how Christianity not only exists alongside academia, but has much to contribute to any scholarly pursuit. Marsden’s (1998) Outrageous idea of Christian Scholarship argued that a Christian worldview can permeate arts and sciences. Carpenter and Ships’ (2019) Making Higher Education Christian summarizes the research to date, argues that colleges need to move from career preparation to teaching justice, sacrifice, anti-consumerism. Gangel’s Toward a harmony of faith and learning (2002) laid out how Christian worldview impacts higher education programs in Theology, church leadership, humanities, sciences, languages, PE. Holmes’ Building the Christian Academy (2001)provided a similar roadmap. Dockery’s Faith and Learning (2012) has 16 essays integrating Christianity with media, sciences, engineering, social work, and so on. Dockery and Morgan’s Christian Higher Education (2018) covers integration in Social sciences, philosophy, humanities, arts, and education. For a robust list of works that have integrated the Christian faith with various disciplines, see this bibliography of faith integration.

The flowchart below depicts the development of thought on faith integration, as described above.

References:

Akers G. H. (1977). The measure of a school. Journal of Adventist Education, 40 (2), 7-9, 43-45.

Badley. (1994). The Faith/Learning Integration Movement in Christian Higher Education: Slogan or Substance? Journal of Research on Christian Education, 3 (1), 13-33

Benne, R. Quality with soul: How six premier colleges and universities keep faith with their religious traditions. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Burtchaell, J. (1998). The dying of the light: The disengagement of colleges and universities from their Christian churches. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Dockery, D. (2012). Faith and Learning. B&H.

Dockery D. and Morgan C.eds. (2018). Christian Higher Education. Crossway.

Gaebelein. (1954). Pattern of God’s Truth. Oxford University Press.

Gangel, K. (2002). Toward a harmony of faith and learning. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock.

Hasker, W. “Faith-learning integration: An overview,” Christina Scholar’s Review 21 no 3 (1992) 239-43.

Holmes, Arthur. (1975). The ides of a Christian college. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Joeckel, S., & Chesnes, T. (2012). The Christian College Phenomenon. Inside America’s fasting growing institutions of higher learning. Abilene, TX: Abilene Christian University Press.

Langer R. (2012). The Discourse of Faith and Learning. Journal of Education and Christian Belief, 16 (2):159-177. doi:10.1177/205699711201600203

Marsden, G. (1994). The soul of the American University. New York: Oxford University Press.

Noll’s (1994) Scandal of the Evangelical Mind. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Wolterstorff, N. (2002). Educating for Life. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker.