By Kenneth Nehrbass

It’s common around the Christian University for professors to start class with a prayer. Actually, students appreciate this- and it shows on their course evals. But does this count as faith integration? After all, it can be hard to integrate the Christian worldview in an algebra class, right? In fact, Kaul et al.’s (2017) study of 2074 faculty at 55 CCCU institutions found that “religion and philosophy instructors are the most likely to integrate faith into their teaching, and professors specializing in computer science, math, and engineering were the least likely” (p. 172).

In many instances, starting class with a prayer (and scripture reading) is better thought of as faith AND learning, the way we would eat steak AND potatoes. It’s not integration like moving leaven through bread—it’s what Benne (2001) referred to as the “add on” model (p. 105)— adding faith to the classroom, but not necessarily integrating it. And the “add-on” model is not only prevalent but preferred by as many as half of the professors at certain Christian heritage schools like Baylor (Lyon, et al., 2005).

Is there anything wrong with the “add on” model? It has some advantages:

- It can be done quickly, without much preparation or experience in faith integration;

- It is fairly non-threatening to students; and,

- It invites students to turn their thoughts toward the Lord, and to see Christian witness around campus.

Then again, the add-on model has one notable disadvantage:

- It can reinforce the notion that faith does not directly impact the academic discipline.

In light of the advantages and disadvantages, it seems reasonable to me that professors should consider beginning class with prayer (and better yet, some scripture and prayer). And those who have been praying at the start of class for a long time should push themselves to go beyond the “add-on model” and see ways they can further integrate the Christian worldview with the course content.

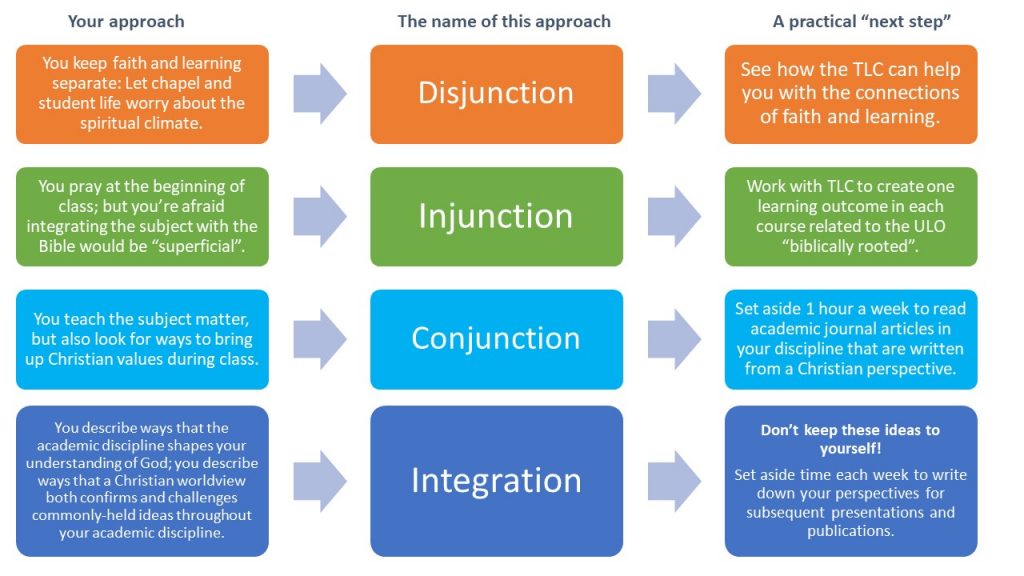

To put it another way, the “add on” model is an earlier “stage” of faith integration, whereas integration comes later. Writing at a time when “stages” were common in empirical studies, Akers (1977) theorized that Christian educators fell into one of four stages of faith integration: Disjunction, injunction, conjunction, and integration. Disjunction separates the Christian co-curricular part of the university from the academic curriculum. Injunction “adds on” spirituality (usually at the beginning of class). Conjunction sees how Christian values can be taught in the curriculum, but keeps the academic discipline intact: It does not allow Christianity to challenge fundamental presuppositions in the guild. Integration creates something new—it allows the Christian worldview to re-shape the academic discipline.

The ethos at CBU is one of faith integration, so the disjunction approach is very unlikely here, though Lyon et al. (2005) noted that such an approach is common at non-CCCU schools that have a Christian heritage.

Take a look at some of the stages and next steps above. What step is coming next for you in your journey? How might the TLC come alongside you? Also, in the comment section, take some time to respond to the questions below (in red).

Akers, G. H. (1977). The measure of a school. Journal of Adventist Education, 40 (2), 7-9, 43-45.

Benne, R. (2001). Quality with soul. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Kaul, C, Hardin, K & Beaujean, A. (2017). “Predicting Faculty integration of Faith and Learning.” Christian Higher Education. 3 (16) 172-187.

Lyon, L; Beaty, M; Parker, J. & Mencken, C. (2005). Faculty Attitudes on Integrating Faith and Learning at Religious Colleges and Universities: A Research Note. Sociology of Religion, 66(1), 61–69.

Questions: How have you seen devotions create something positive in your classroom? Where do you place yourself in the following graphic? Are you at a stage that isn’t mentioned in the graphic? We’d love to hear from you in the comments section.