By Kenneth Nehrbass

Professors often specify in their rubrics for term papers and presentations that the cited sources should be current and scholarly. And of course, they try to model this selectivity by assigning readings that meet the same criteria. This desire is in line with Quality Matters’ Specific Review standard 4.4: “instructional materials represent up-to-date theory and practice in the discipline.”

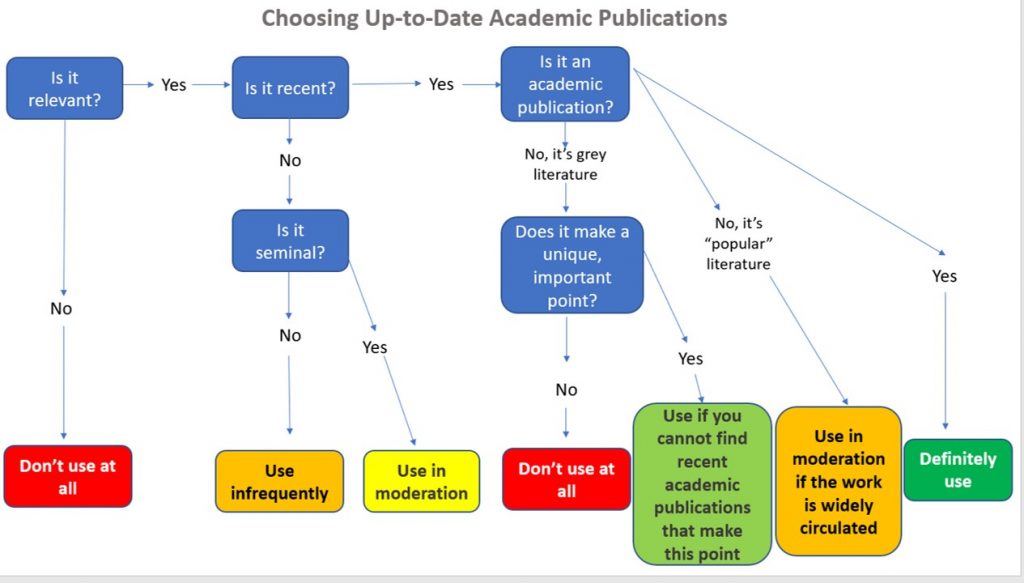

But what if you found something on a blog that you think your students would benefit from? And what if your student wants to cite a conference abstract, or a dissertation? These types of sources are “published” on the web, but are sometimes referred to as grey literature, rather than bona fide academic sources, because they have not been subject to a peer-review process. Does the over-use of grey literature set a bad example for students? It depends on a number of factors:

- Was the work seminal (meaning that it started a new theory, not just that it is well known)?

- Is the work recent for your discipline (recent, for education, is different than recent for mathematics or biblical studies)?

- If the work is not published, does it provide an important perspective that is not found in the academic literature?

Actually, the use of grey literature can be very productive. It can:

- Encourage students to be on the lookout for future academic publications on these ideas.

- Point out areas that students could do further research to confirm or refute the claims in the grey literature.

Deciding whether to use a source is not black-and-white. But the answers to the above questions can help narrow down the choice. For example—much of the literature on cross-cultural discipleship is often non-academic (little empirical research has been done, and little has been published in peer-reviewed journals on the subject). Therefore a class on cross-cultural discipleship may need to rely on popular theorists and grey literature because those are the only widely circulated ideas on the subject.

The graphic below provides several criteria for choosing a source- and recognizes that some types of sources should be used more frequently than others (and some not at all).

Image Credit: Ken Nehrbass

When using grey literature or popular literature, it may be a good idea to explain to the students (or readers) why you are using these sources (i.e., because they are the only ones available, or because they are influential in your field). And you may also explain the limitations of this literature (i.e., it lacks empirical evidence or has not been peer-reviewed).

How would you modify the above graphic to help students in your field make decisions about incorporating sources? Let us know in the comments section.